Welcome to Quiet Reading, a weekly refuge for our shared humanity, inspired by authors, books, and this world of marvels.

Last week I issued an open invitation for video recordings of the poems we carry in our blood. By the time you could say “The Spangled Pandemonium is missing from the zoo,”

had posted a delightful example on Substack Notes - a recitation in the rain.1 By sheer coincidence, posted about a remembered poem that reset his afternoon energy in the latest edition of his popular newsletter . (No surprise for those who’ve been here for awhile: “The Owl and the Pussycat” is an old favorite of mine, too.)If you carry a poem in your blood or would like to ingest and metabolize one by October 25th, please join in with your own verses old or new, borrowed or blue! Guidelines come at the end of last week’s post.

I’ve been thinking this week about whether I carry prose words in the blood the way I carry poems. Of course the answer is yes, as I’m sure it is for you. But the memory is different. What lingers is only a word here or there like “dignity” or “conscience” or “free,” along with sometimes an emotional memory of the scene of first reading — the scene, if you will, of impact.

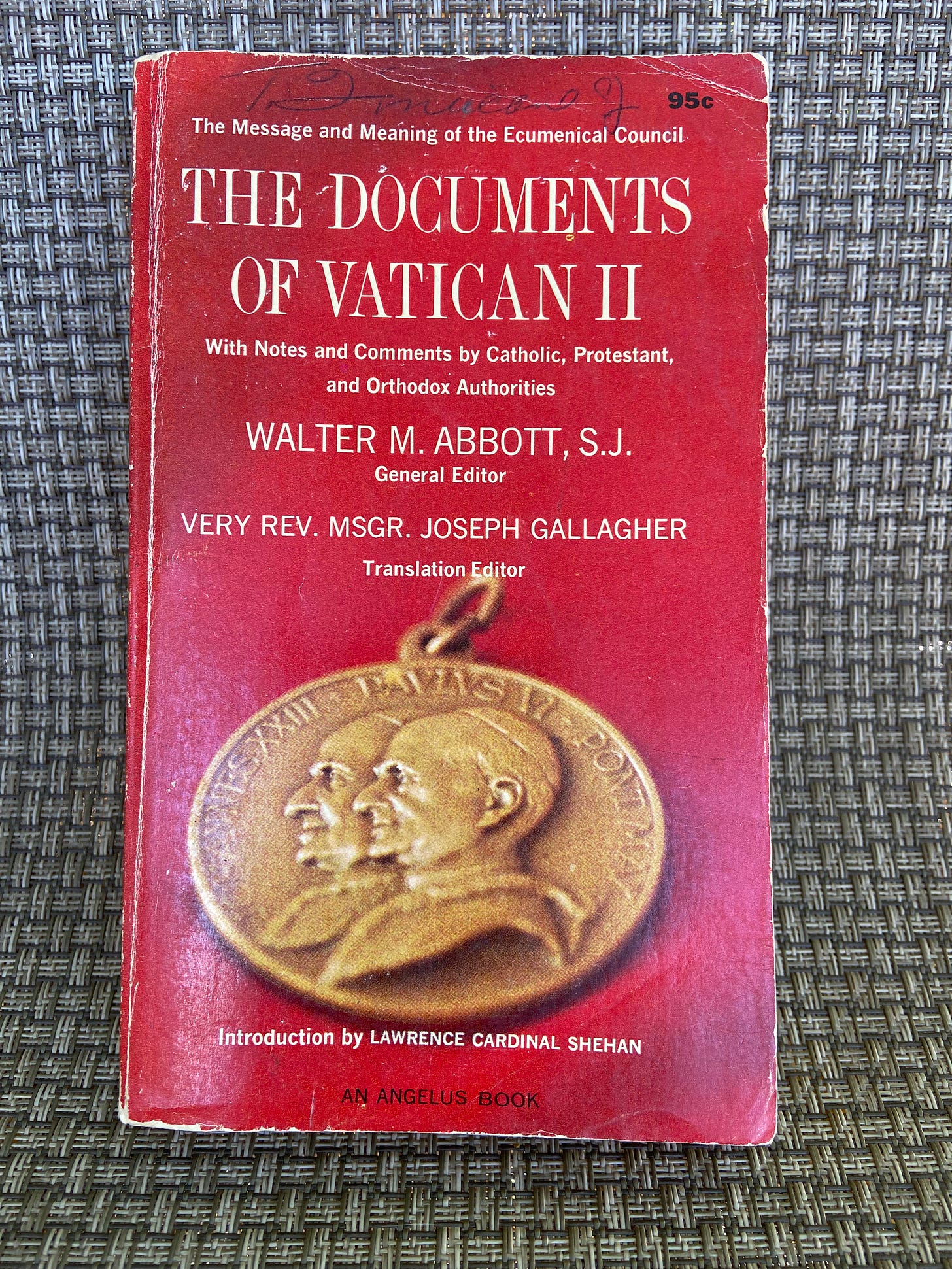

A work of prose that sank through the skin into my cells many decades ago was perhaps the unlikeliest book ever to move a teenager in the history of the world.

I kid you not: at sixteen or seventeen I felt a thunderbolt of truth on page 675 of The Documents of Vatican II.

The unlikeliest book ever to move a teenager

Upstairs one day in my mother’s library - maybe under sunny skies, maybe with rain pelting the windows, I was kvetching about the Catholic Church (if Catholics are allowed to kvetch). The rules and doctrines seemed out of touch for a young person in the last quarter of the twentieth century. I was not a kid anymore. I had my own opinions. I did not see how any thinking person could call themselves Roman Catholic.

My mother turned to a bookshelf and took down a plump red paperback. Thumbing pages with definite intent, she found the one she wanted and passed the book to me.

“Declaration on Religious Freedom,” read the chapter title on page 675. I flipped to the front cover. The Documents of Vatican II, she had handed me. I looked at my mother with some skepticism. Religious freedom, as everyone knew, was for Protestants.

“Read,” she ordered, pointing her shapely, home-manicured fingernail at the arbiter of all debates, the primary text. More curious than obedient, I complied.

A sense of the dignity of the human person has been impressing itself more and more deeply on the consciousness of contemporary man, the document began, and the demand is increasingly made that men should act on their own judgment ….

In those days, I did not question whether I had a share in “the consciousness of contemporary man.” Of course I did. I could swing both ways, female in the selection of bathrooms, “man” when I read a text like this one. Only later, in graduate school, would I learn that history had not always admitted xx-chromosome-bearers like me into the privileges of all-manhood. But that’s another story. In my early reading, I was contentedly androgynous.

Not far down the page: On their part, all men [that’s me] are bound to seek the truth, especially in what concerns God and His Church, and to embrace the truth they come to know, and to hold fast to it.

Phrases landed with me like lines in a poem:

their own judgment,

all … bound to seek the truth … and to hold fast to it,

human conscience,

impressing itself more deeply,

and most of all

the dignity of the human person.

Dignitatis Humanae, the document was called: Of human dignity, or, Of the dignity of human persons.

I think this was the day the word “dignity” became entwined with personhood in my imagination — and still it sits with primacy there.

The word “conscience” appeared often in the declaration, indicating a responsibility on the part of all persons me to find their my own path to truth. There was no mistaking the primacy of individual judgment in passages like this: “[H]e is not to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his conscience. Nor, on the other hand, is he to be restrained from acting in accordance with his conscience,” and “[T]he exercise of religion, of its very nature, consists before all else in those internal, voluntary and free acts whereby man [me] sets the course of his life directly toward God.”

Wow. To a teenager, few words confer dignity like “voluntary and free” — especially from the hand of a parent.

It may have been this day that I began to translate religious language into my own idiom. I was not at all sure (i) that life had an “end and purpose” or that (ii) I would ever be comfortable referring to that end and purpose as “God,” but Dignitatis Humanae allowed me to believe what I believed. My job was to inform my free conscience as well as I could and “hold fast” to what it showed me.

As my mother knew all along, I could live with that.

Dignity in civic life

This morning I am sorting through the mail, most of which wants me to vote this way or that in the upcoming election. I will make time to read all of it. My absentee ballot sits in a special place, waiting for me to inform my conscience about decisions that do not make the news.

In one of my classes, the students (mostly eighteen- and nineteen-year-olds) are researching political questions and candidates in order to write about them.

I told them when we started this unit: You are safe here to ask any question in good faith. Even if you change your mind later and wish you had voted differently in this election, you will not be the first voter to change your mind. Do your best to answer your questions and cast your vote. No one here gets to bully, shame, or intimidate you.

In my class, we treat politics with the dignity of a truth-seeking discourse — like poetry or ideal religion.

The best thing I can give my students is a mirror of their dignity as free persons.

Dignitatis Humanae is a poem in my blood.

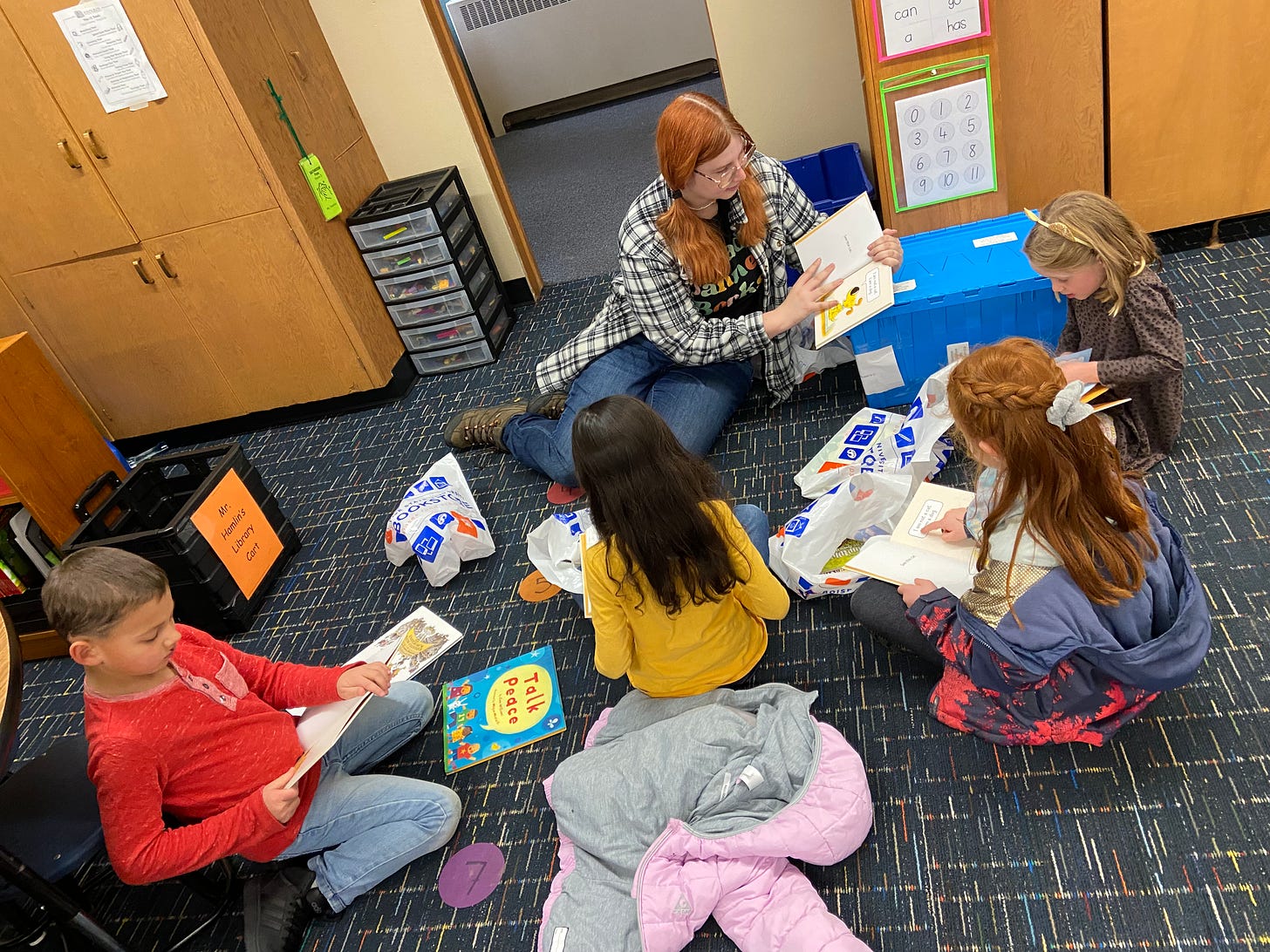

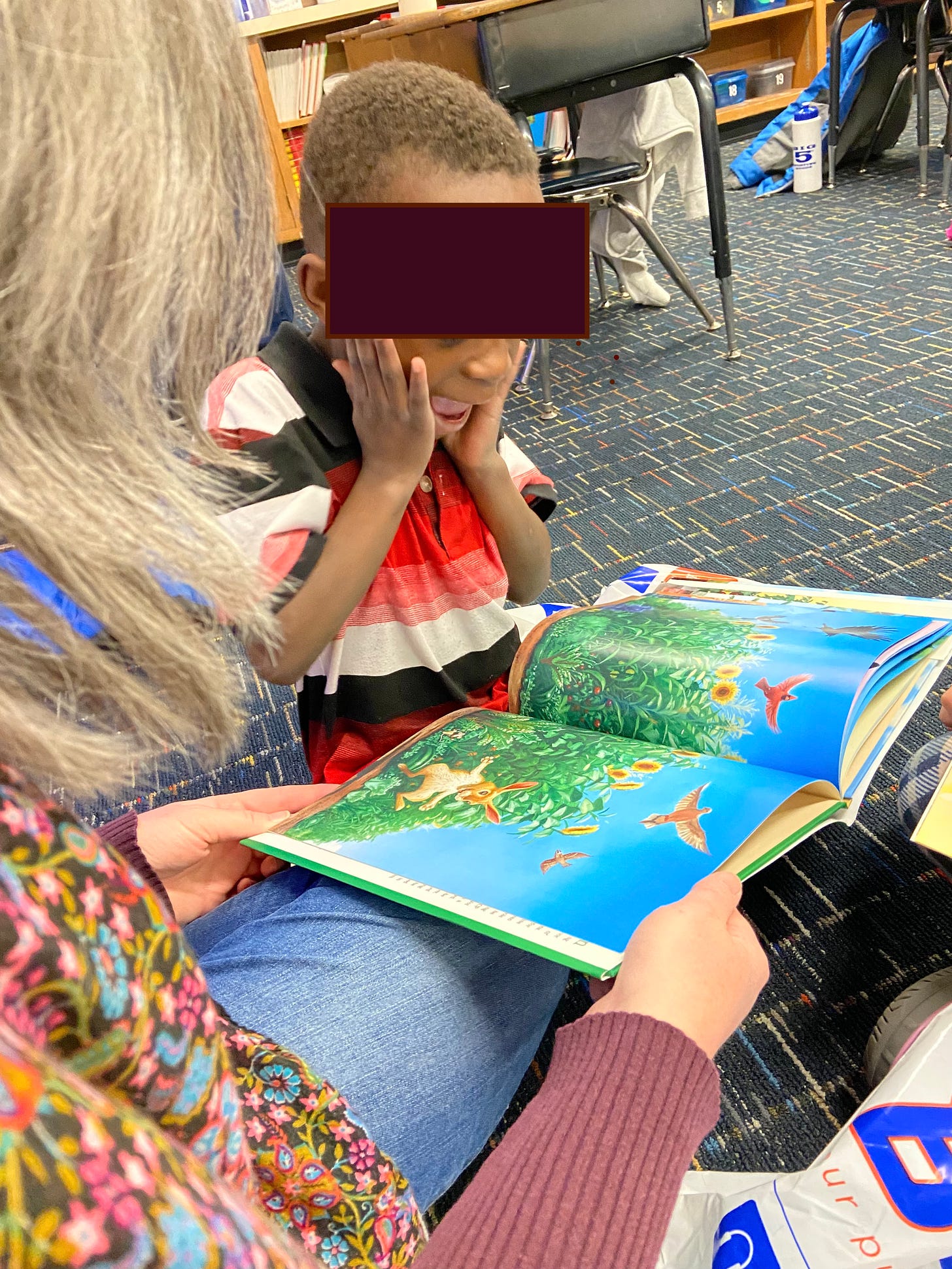

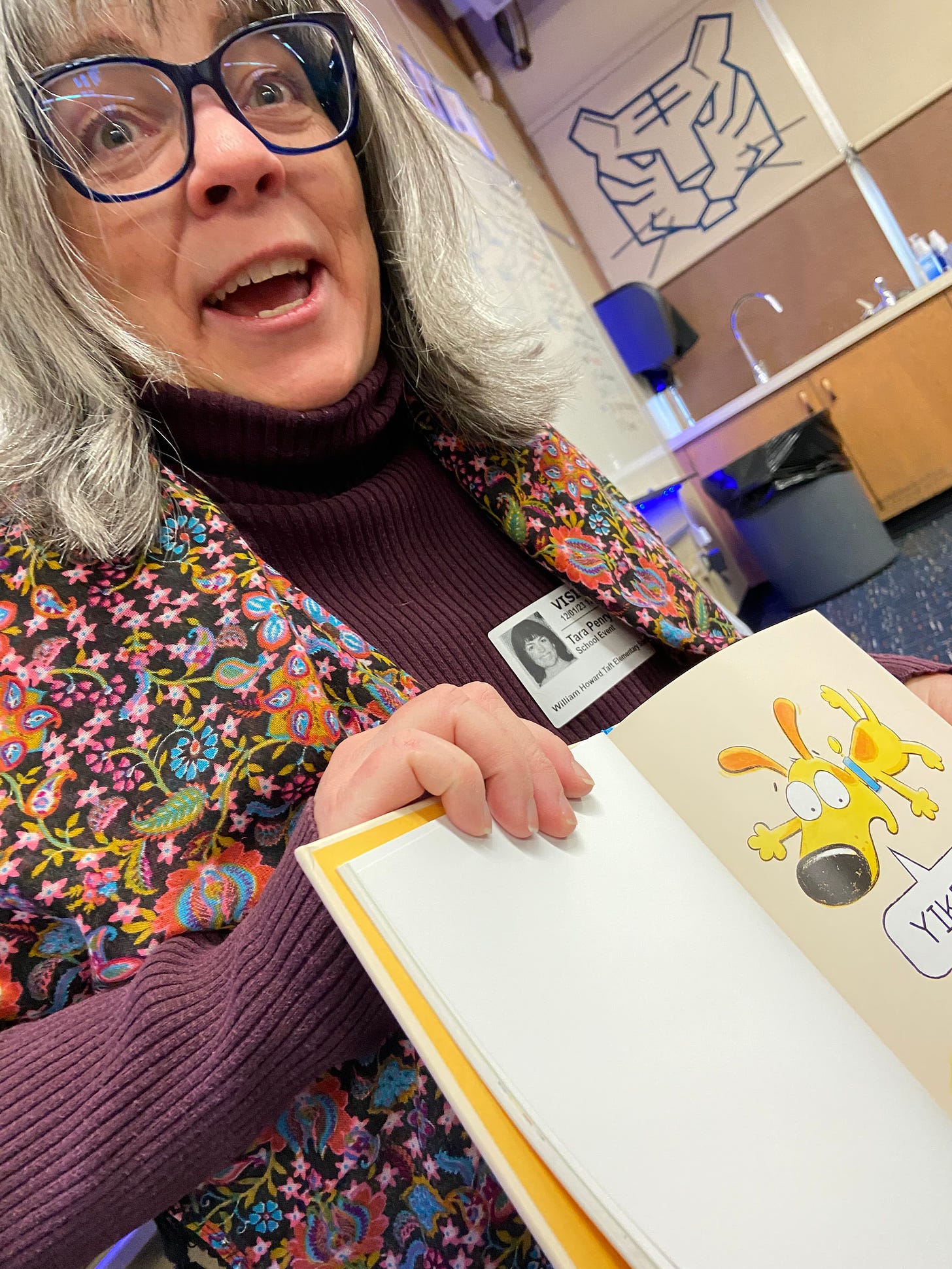

What I picture now when I talk about books and dignity

(A tiny photo essay)

So, you see, you have nothing to fear from joining in our little celebration of language in the blood. Choose a poem (or prose-poem). Commit it to memory. Take a video of yourself reciting it. Set to post on your Substack Oct. 25. Tag me. You can find a crowd of suggested poems here.

Your Turn

What work of prose has moved you like a poem?

Have you chosen a poem to memorize and recite yet for “Poems to Carry in the Blood”?

Did you know that Catholics are supposed to follow their conscience, if it comes down to a difference of opinion with authority?

If you are not familiar with the four-stanza poem called “The Spangled Pandemonium,” an anthology favorite by someone named Palmer Brown, let’s remedy that forthwith. I believe it is the first poem I memorized for school, in second grade. How proud I was of all these stanzas! It felt like I had memorized a scroll reaching down to my toes:

The Spangled Pandemonium Is missing from the zoo. He bent the bars the barest bit, And slithered glibly through. He crawled across the moated wall, He climbed the mango tree, And when his keeper scrambled up, He nipped him in the knee. To all of you a warning Not to wander after dark, Or if you must, make very sure You stay out of the park. For the Spangled Pandemonium Is missing from the zoo, And since he nipped his keeper, He would just as soon nip you!

Subscribe to Quiet Reading with Tara Penry

A weekly refuge for our shared humanity inspired by authors, books, and this world of marvels.

“A Country Road Song” by Andre Dubus, a breathtaking essay from his collection Meditations from a Movable Chair. I must have read it dozens of times, drawn by the gorgeous precision of his language and author’s hard-won insight on the seasons of a fragile human life. Any writer can learn from the structure of this essay. One of my own most-shared essays here is a quiet homage to this cathedral of words. Only the final paragraph can be found online but it’s worth buying the book to have this talisman.

_Tinkers_ by Paul Harding. You won't believe how elegant and moving this novel is until you read it. A stirring elegiac novel that abandons linear narration for the purpose of revealing the nature of existence, the love that binds us in the face of life’s betrayals. The award of the Pulitzer in 2010 is a tribute to the fact that literature published by a small press can find voice and then be heard by readers in search of transformational art.