She Wrote a Classic in the Laundry Room

She knew she had to write -- but how?

The Once and Future Author is a series of tiny biographies of successful authors in their early years. Most biographies are written backward from a person’s fame to their backstory. These are written as though future fame is not assured. The author is just another person with a future to figure out, like you or me.

You can find other posts in this popular series here.

It is not hard to imagine the eldest Miss Laidlaw’s alternatives, had there been no scholarship. How she would have continued to keep house for her parents and younger siblings while her mother’s Parkinson’s disease progressed. How a rural teaching job would have taken her far from home for modest pay. How a marriage of necessity might have scuttled her writing.

By the age of fourteen, “Alys” (as she signed herself) was “serious” about writing. Her English teacher, a woman with a university education, often read her prize student’s compositions aloud. Classmates prophesied that Alys would be a famous writer. More than one person put the idea of university in her head.

But the Laidlaw family had no money to support a daughter through higher education. To earn a two-year scholarship, Alice Ann needed high placements on exams in eight or more subjects. The high school French teacher stayed after school to tutor her in German so she could take a fourth literature and composition exam — English, French, Latin, German. Alice Ann also tested in Botany, History, and Zoology. As a backup plan, she applied for teaching jobs and got an offer from a country school three or four days’ drive to the northwest.

Fortunately, Miss Laidlaw took first or second place in every exam. A full tuition scholarship of $125 per year opened a path to the regional public university in the next county. A second scholarship gave her enough cash to live frugally as a boarder. Shortly after her eighteenth birthday in the summer of 1949, the responsible big sister of Sheila and Bill left home for the University of Western Ontario like approximately two thousand other undergraduates, many of them recent veterans of World War II.

Publication and Marriage

Alice Ann Laidlaw distinguished herself as a writer immediately, publishing stories in the college magazine both years of her attendance while earning honors in English with a creative writing emphasis. She loved her university years. As she told her biographer much later, “Those are the only two years of my life without housework. ... [I]t was all reading and writing, studying.”

With dark wavy hair hanging thickly to her shoulders and a pretty smile, she caught the eye of a tall, blonde History major who loved art and classical music. After college, Jim and Alice married in her parents’ living room and took the train west to the fourth largest port city in North America, where he had a job. She was twenty. He was twenty-two.

The young housewife did not love the port city, or the habit of neighbor women dropping in for chats about diaper washing and the organization of cupboards, but at least her husband admired and supported her writing. (The summer after they married, he gave her a typewriter for her twenty-first birthday.)

Through the 1950s and ‘60s, while housekeeping and caring for two daughters, then three, the former Miss Laidlaw wrote stories. A radio producer accepted the first of these stories in 1951, before the wedding, and encouraged the young author to send more. Although at first he rejected more than he accepted, he became a mentor, telling her candidly when she “failed to rise above somewhat commonplace and tedious material,” teaching her to double-space her typescripts, and suggesting quality magazines for her submissions. With his encouragement, she continued to write, though she later told an interviewer, “I didn’t foresee at all that it would be such a long haul to get anything written that would be any good at all. Mostly, all through my twenties all I did was read.”

That was a bit of an exaggeration. During her twenties and thirties, she slowly built a portfolio of publications in magazines while her oldest two daughters grew into their teens. As one daughter explained much later,

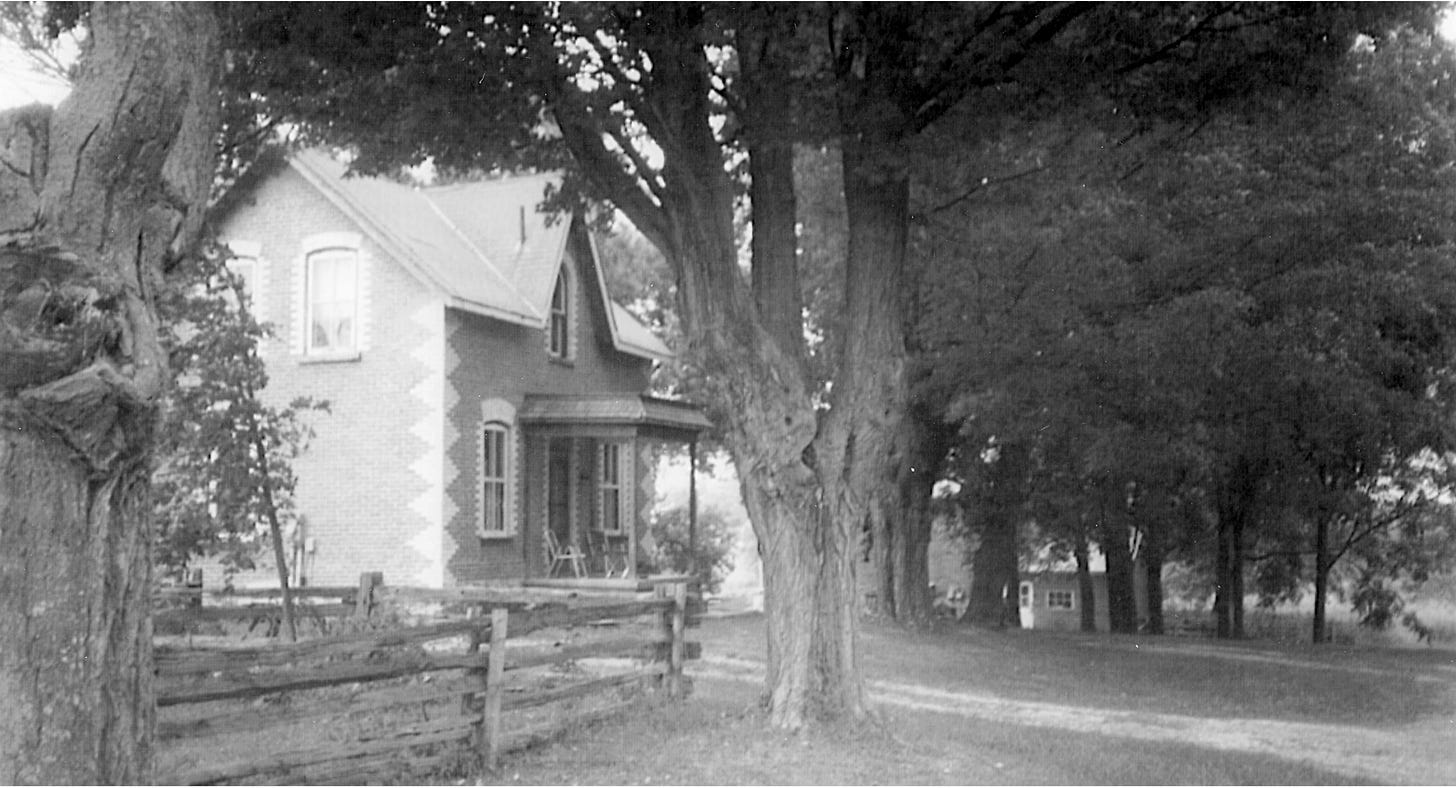

Housework was nothing new; from the age of twelve she had been doing all the work at home because her mother had Parkinson’s disease. She had been composing poems and stories while she made the beds, or washed the dishes, or hung up the laundry. … The room in which she wrote [her second book] was a laundry room, and her typewriter was surrounded by a washer, a dryer, and an ironing board.

She wrote while pregnant with her first child and received $300 for a story that appeared one month after her daughter Sheila’s birth in 1953. She wrote facing her six-month-old baby in the crib. She “dash[ed] back to the typewriter after the grandparents had gone, when I was having a nap, when the neighbours finally decamped.” She wrote in her bedroom or (briefly) in a rented office until, in the early 1960s, she found she could not write at all.

She meant to write a novel and found she could not do it at home. “A house is all right for a man to work in,” she wrote at this time, but “A woman who sits staring into space, into a country that is not her husband’s or her children’s is … known to be an offense against nature.” Her typing created “a tension in the air” of the house.

And yet getting out of the house did not solve the problem. For four months she rented an office space a few blocks away, where she wrote one story called “The Office” and otherwise “spent hours staring at the walls and the Venetian blinds, drinking cups of instant coffee with canned milk.” Instead of a novel manuscript, she got an ulcer. For a year, she felt “a total blockage. … I could think of things but I couldn’t write them.”

After ten years of fitting such strange work around a “normal life” as a wife and mother, “the black life of the artist” was expressing itself in panic attacks and words that wouldn’t come.

From Stories to Books

Relief arrived in a break from writing. In 1963, the husband and wife together decided to open a bookstore in a university town. Alice felt better suited to the new city, and later she described the next few years as the happiest of the marriage, when she and her husband worked hard for a common goal. They cleaned up “a long, dark, dirty, low-rent store with an old-fashioned entrance deep between two display windows. A tanner’s shed at the back. Once it had been a hat shop.” They opened for business in September and sold an eclectic mix of new paperbacks. Jim had found his calling. Over the decades, the store would grow into more space and an international reputation.

But for Alice, selling books was not enough.

In 1961, there had been talk with her mentor in radio about making a collection of her stories. An editor wrote to check on her in 1964. She answered, “I’ve almost forgotten I am a writer.” She wrote just two new stories in the first three years of keeping a bookstore. In the fall of 1966, the family bought a stately Tudor-style house, and another daughter was born (Alice’s fourth birth and third surviving child in thirteen years). In February 1967, Alice apologized to the interested editor for having no new stories to add to a book, but she hinted that she was working on a novel when she could find the time. It was in the Tudor-style house that the oldest daughter, Sheila, now a teenager, remembered her mother typing at her novel in the laundry room.

And yet a collection of stories did come together around bookstore shifts and new baby feedings. From stories she had written since the early fifties, Alice, her mentor in radio, and her publisher assembled a book at last.

In March 1969, Alice got word that her book, Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), had been nominated for the highest literary prize in the country, Canada’s Governor General’s Award. Two months later, she learned that she had won the prize.

From First Book to Nobel Prize

With the publicity that accompanied the award, you might say that Alice Laidlaw Munro’s literary career was launched in 1969, but she had been writing and publishing as much as she could, in whatever form she could, since starting college twenty years earlier.1

Nor did a book put her on easy street. She had yet to acquire an agent or a name outside Canada; so far, she had only rejections from The New Yorker magazine, where eventually she would publish 62 stories. She had yet to manage the awkward transit between British Columbia, home to her daughters, and Ontario, the home to which she would return in her separation and divorce from Jim Munro in the 1970s.

If her first book “exposed” her “previously secret writer’s life” and lent her “a minor celebrity status in Victoria,” where she was known as co-owner of Munro’s Books (Thacker, p. 252), her next one — the novel-in-stories written in the laundry room — Lives of Girls and Women (1971), expanded her audience with U.S. and British editions. It spoke to “the feminist temper of the times” (Thacker, p. 252), as protagonist Del tried to work her way free of stifling social conventions. “When I bit Mary Agnes,” admits the book’s speaker in one story, “I thought they would all hate me, and hate seemed to me so much to be coveted, then, like a gift of wings” (Lives of Girls and Women, p. 53).

Alice Munro was growing the wings she needed to end her marriage and return home to Ontario. Having relied on Robert Weaver, the mentor in radio, for feedback and advice for years, she met more people who could help her — editors, publishers, the American agent Virginia Barber. In 1977, she finally cracked the difficult New Yorker with the first of dozens of stories she would publish there. During the 1970s, she reconnected with an old college acquaintance, who became her second husband. In Victoria, Jim Munro also remarried. He died in 2016.

Remember when I said that Jim supported Alice’s writing from the beginning? In 2002, Alice Laidlaw Munro’s home town of Wingham, Ontario, dedicated a literary garden in her honor. Alice Munro was there with many friends — “almost five hundred people … on a beautiful summer day,” reported her biographer Robert Thacker, who also had the sensitivity to notice: “Among the contributors listed in the program was Munro’s Books” — the store thousands of miles away still owned by Jim Munro (Thacker, p. 510).

By then, Alice Munro - who continued to publish under the name she took in 1951 - accepted that the short story was her native form. She wrote steadily with the aid of her agent and a familiar team of editors and publishers. Between her first book in 1968 and her last one, Dear Life, in 2012, she published a new story collection every three or four years, each book garnering similar praise. She could evoke the depth of a novel in a short story, people said. She depicted rural life with precision, people said. She dignified the short story as the equal of any artistic mode, not just a stepping stone to a novel, they said.

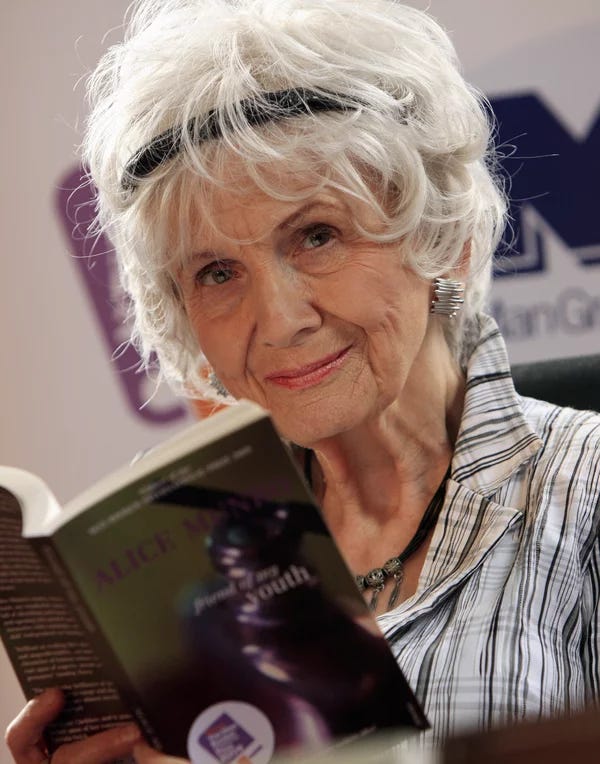

Looking back from her Nobel Prize for literature in 2013 or her 2024 obituary in the New York Times, a twenty-first-century reader might see only the smiling, still-attractive face of an older woman with lovely white hair and keen eyes. With thanks to her biographers, we know instead that Alice Munro needed decades of vision and tenacity, not to mention timely support from others, to get from her classmates’ prediction to her eventual fame as an author. She boarded a train in 1951 for a new life in British Columbia. Just over a decade later, short of breath with anxiety, she took the ferry with her small family to Victoria for a fresh start in a bookstore. Still another decade later, at wits’ end again, she began to move home to Ontario. Like many of us, she found her way by slow trial and error.

Alice Munro told stories of plain people. She may have become a literary icon by the time of her death last month, but she was always a hard-working, exacting writer with no clairvoyance around the next bend.

Perhaps like you or me?

Coming Up

On June 13, I’m delighted to share an interview with Robert Thacker, Alice Munro’s biographer and leading international scholar of her archive. We’ll pick up her story where this post leaves off, talking about her return home to Ontario, how Thacker became aware of her in the mid-1970s, how she thought about feminism, and other topics.

If you are a writer on Substack, you are invited to post your own tribute to Alice Munro one month from the day of her death. Here is how to have your post included in the Substack writers’ memorial.

Here at Quiet Reading, you can expect between now and June 13: A scene of quiet reading inspired by the late laureate, and my answer to the question, “What’s so great about Alice Munro?” Hear Professor Thacker’s answer on June 13.

Resources

Alice Munro's life in photos by Professor Robert Thacker. Follow the link to view photos, key dates, and quotations from books in 19 slides compiled by Munro’s biographer.

Robert Thacker, Alice Munro: Writing Her Lives (McClelland & Stewart, 2005). Updated edition, 2011.

Much of this post was taken from the research in Thacker’s detailed and engaging biography. Pages cited or quoted above from the 2005 edition: 84-87, 93-100, 105-116, 120, 173-78, 182-83, 196, 210-11, 252, 510.

Robert Thacker, Alice Munro’s Late Style (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023).

Sheila Munro, Lives of Mothers & Daughters: Growing Up with Alice Munro (McClelland & Stewart, 2001).

Pages cited or quoted above: 28-35.

*

Special thanks to Bob Thacker for the slides and his dedication to the work of Alice Munro for the last fifty years! He’ll be back with more on June 13.

P.S. If you “Share” this post - and I hope you will - remember not to mention exactly who it’s about. Some people will figure it out right away. Others may not. Isn’t it fun to guess? 😉

July 9, 2024 - With the exception of this footnote, this post appears as it was originally published in June. As of July 7, Munro’s readers now know how her youngest daughter was isolated and hurt by her mother’s response when she learned that her second husband had abused her youngest daughter years earlier. This post was written to show the hardships and sacrifices of Munro’s literary life, but without awareness of the specific costs paid by her children. See the headnote and links in my updated introduction to the Alice Munro Substack Virtual Memorial for more on Andrea Skinner’s revelations.

Tara, I enjoy your windows into writers I might not otherwise find. I started an important part of my real liberal education as a kid when I would find an author who captured my imagination, read everything they wrote, which invariably gave me leads to other writers and so on and so forth. It’s been a journey of discovery.

Now I am beginning to depend on you to bring writers to my attention I might otherwise miss. Thanks so much for helping keep my journey of discovery alive.

Perhaps it says more about me than about Alice Munro that I'm comforted by her panic attacks and the "words that would not come." It's a good reminder that writing is a lifelong apprenticeship, and that it takes that kind of commitment to catch a break, and to be ready to seize it when it comes. It's a curious thing, this faith that learning how to be alone in a room will end up producing something of value to others. But if done well, we're not really alone in that room, are we?

You make me wonder now where Alice would be in the current landscape, whether she'd be a Substacker or still plying the magazines. Impossible to know.