Welcome to Quiet Reading, a weekly refuge for our shared humanity, inspired by authors, books, and this world of marvels. I halted this past weekend’s post while the southeast was cleaning up and finding survivors from Helene, and out here in Idaho, thousands of miles to the west, firefighters diverted a local fire away from our city, into the mountains. Nothing I had begun to write seemed to meet the moment. So I hosted a small birthday party for my sixteen-year-old and was satisfied. With the next Gulf hurricane due to make landfall in west central Florida tonight, I am dipping into beloved books for reminders of the majesty of weather.

I know friends living in or near the Gulf of Mexico and the Appalachians need no reminders. These are for the rest of us.

The Little Mermaid

Far out at sea, the water is as blue as the petals of the prettiest cornflowers and as clear as the purest glass. But it’s very deep out there, so deep that even the longest anchor line can’t touch bottom. You would have to pile up countless church steeples, one on top of the other, to get from the bottom of the sea all the way up to the surface. The sea people live down there.

Now you mustn’t think for a moment that there is nothing but bare, white sand down there. Oh, no! The most wondrous trees and plants grow at the bottom of the sea, with stalks and leaves so supple that they stir with life at the slightest ripple in the water. The fish everywhere, large and small, dart between the branches, just the way birds fly through the trees up here. At the very deepest spot of all stands the castle of hte Sea King. Its walls are coral, and the tall, arched windows are made of the clearest ambrr. The roof is formed of shells that open and close with the current. It’s a beautiful sight, for each shell has a dazzling pearl, any one of which would make a splendid jewel in a queen’s crown.

— Hans Christian Andersen, from “The Little Mermaid,” trans. by Maria Tatar.

💧 💧 💧

Jane Eyre

My eyes were covered and closed: eddying darkness seemed to swim round me, and reflection came in as black and confused a flow. Self-abandoned, relaxed, and effortless, I seemed to have laid me down in the dried-up bed of a great river; I heard a flood loosened in remote mountains, and felt the torrent come: to rise I had no will, to flee I had no strength. I lay faint, longing to be dead. One idea only still throbbed life-like within me — a remembrance of God: it begot an unuttered prayer: these words went wandering up and down in my rayless mind, as something that should be whispered, but no energy was found to express them —

‘Be not far from me, for trouble is near: there is none to help.’

It was near: and as I had lifted no petition to Heaven to avert it — as I had neither joined my hands, nor bent my knees, nor moved my lips — it came: in full heavy swing the torrent poured over me. The whole consciousness of my life lorn, my love lost, my hope quenched, my faith death-struck, swayed full and mighty above me in one sullen mass. That bitter hour cannot be described: in truth, ‘the waters came into my soul; I sank in deep mire: I felt no standing; I came into deep waters; the floods overflowed me.’

— Charlotte Brontë, Chapter 26, Jane Eyre

💧 💧 💧

Refuge

In 1975, the Utah State Legislature passed a law stating Great Salt Lake could not exceed 4202'. Almost ten years later, at lake level 4206.15', Great Salt Lake is above the law. What lasso can you use to corral the West’s latest outlaw?

. . .

Great Salt Lake has swallowed the causeway that led to Antelope Island. Gone. The road has been erased. Gentle waves cross over each other from north and south. A sign half submerged reads, SPEED LIMIT 45 m.p.h. It must apply to the birds. Thirty miles to the north, the Bird Refuge is underwater.

. . .

The foreman turns around. “No matter what they tell you on the news, the lake’s still risin’.”

— Terry Tempest Williams, Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place, pp 58-64

💧 💧 💧

A California Gold Rush yarn

When the waters were up at Jules’ there was little else up on that monotonous level. For the few inhabitants who calmly and methodically moved to higher ground, camping out in tents until the flood had subsided, left no distracting wreckage behind them. A dozen half-submerged log cabins dotted the tranquil surface of the waters, without ripple or disturbance, looking in the moonlight more like the ruins of centuries than of a few days. … People took it naturally; the water went as it had come, slowly, impassively, noiselessly; a few days of fervid Californian sunshine dried the cabins, and in a week or two the red dust lay again as thickly before their doors as the winter mud had lain. … There was even a singular compensation to this amicable invasion; the inhabitants sometimes found gold in those breaches in the banks made by the overflow.

[An outsider, Miles Hemmingway, comes to town one season while the water is high and asks, with exasperation, why the locals don’t build their houses on higher ground with a levee at the high water mark.]

“Hev you ever heard what the highest water-mark was?” said the first speaker, turning to one of the loungers without looking at the secretary.

“Never heard it — didn’t know there was a limit before,” responded the man.

The first speaker turned back to the secretary. “Did you ever know what happened at ‘Bulger’s,’ on the North Fork? They had one o’ them levees.”

“No. What happened?” asked the secretary impatiently.

“They was fixed suthin’ like us,” returned the first speaker. “They allowed they’d build a levee above their highest water-mark, and did. It worked like a charm at first; but the water hed to go somewhere, and it kinder collected at the first bend. Then it sorter raised itself on its elbows one day, and looked over the levee down upon whar some of the boys was washin’ quite comf’ble. Then it paid no sorter attention to the limit o’ that high water-mark, but went six inches better! Not slow and quiet like ez it uster to, ez it does here, kinder fillin’ up from below, but went over with a rush and a current, hevin’ of course the whole height of the levee to fall on t’other side where the boys were sluicing.”

He paused, and amidst a profound silence, added, “They say that ‘Bulger’s’ was scattered promiscuous-like all along the Fork for five miles. I only know that one of his mules and a section of sluicing was picked up at Red Flat, eight miles away!”

— From Bret Harte, “When the Waters Were Up at Jules’”

(Harte’s best-known flood happens in “The Luck of Roaring Camp,” which is also a much better story than the one I’ve just quoted. If you want to read more from Harte, start there.)

💧 💧 💧

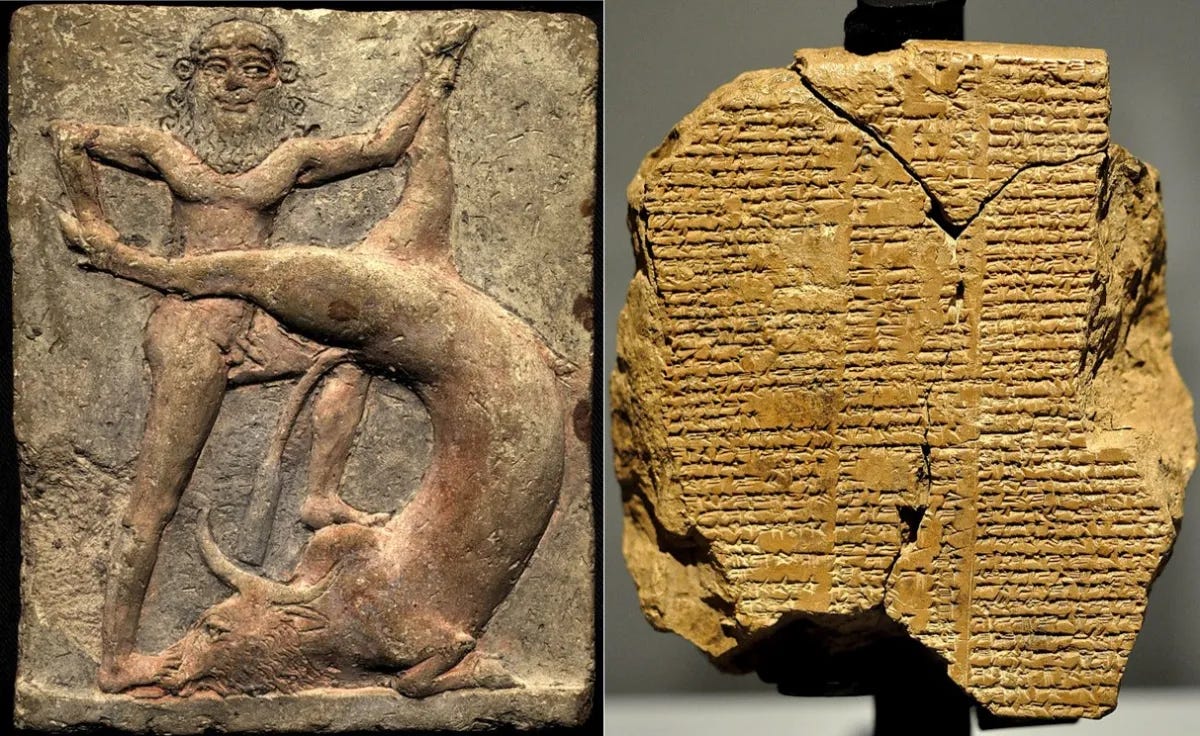

The Epic of Gilgamesh

With the first light of dawn a black cloud came from the horizon; it thundered within where Adad, lord of the storm was riding. In front over hill and plain Shullat and Hanish, heralds of the storm, led on. Then the gods of the abyss rose up; Nergal pulled out the dams of the nether waters, Ninurta the war-lord threw down the dykes, and the seven judges of hell, the Annunaki, raised their torches, lighting the land with their livid flame.

A stupor of despair went up to heaven when the god of the storm turned daylight to darkness, when he smashed the land like a cup. One whole day the tempest raged, gathering fury as it went, it poured over the people like the tides of battle; a imam could not see his brother nor the people be seen from heaven. Even the gods were terrified at the flood, they fled to the highest heaven, the firmament of Ann; they crouched against the walls, cowering like curs. Then Ishtar the sweet-voiced Queen of Heaven cried out like a woman in travail: "Alas the days of old are turned to dust because I commanded evil; why did I command thus evil in the council of all the gods? I commanded wars to destroy the people, but are they not my people, for I brought them forth? Now like the spawn of fish they float in the ocean." The great gods of heaven and of hell wept, they covered their mouths.

For six days and six nights the winds blew, torrent and tempest and flood overwhelmed the world, tempest and flood raged together like warring hosts. When the seventh day dawned the storm from the south subsided, the sea grew calm, the, flood was stilled; I looked at the face of the world and there was silence, all mankind was turned to clay.

The surface of the sea stretched as flat as a roof-top; I opened a hatch and the light fell on my face. Then I bowed low, I sat down and I wept, the tears streamed down my face, for on every side was the waste of water. I looked for land in vain, but fourteen leagues distant there appeared a mountain, and there the boat grounded; on the mountain of Nisir the boat held fast, she held fast and did not budge. One day she held, and a second day on the mountain of Nisir she held fast and did not budge. A third day, and a fourth day she held fast on the mountain and did not budge; a fifth day and a sixth day she held fast on the mountain.

When the seventh day dawned I loosed a dove and let her go. She flew away, but finding no resting-place she returned. Then I loosed a swallow, and she flew away but finding no resting-place she returned. I loosed a raven, she saw that the waters had retreated, she ate, she

flew around, she cawed, and she did not come back. Then I threw everything open to the four winds, I made a sacrifice and poured out a libation on the mountain top.— From “The Story of the Flood,” The Epic of Gilgamesh, transl. by N. K. Sandars

💧 💧 💧

Genesis

Chapter 7

17 For forty days the flood kept coming on the earth, and as the waters increased they lifted the ark high above the earth. 18 The waters rose and increased greatly on the earth, and the ark floated on the surface of the water. 19 They rose greatly on the earth, and all the high mountains under the entire heavens were covered. 20 The waters rose and covered the mountains to a depth of more than fifteen cubits. 21 Every living thing that moved on land perished—birds, livestock, wild animals, all the creatures that swarm over the earth, and all mankind. 22 Everything on dry land that had the breath of life in its nostrils died. 23 Every living thing on the face of the earth was wiped out; people and animals and the creatures that move along the ground and the birds were wiped from the earth. Only Noah was left, and those with him in the ark.

24 The waters flooded the earth for a hundred and fifty days.

Chapter 8

1 But God remembered Noah and all the wild animals and the livestock that were with him in the ark, and he sent a wind over the earth, and the waters receded. 2 Now the springs of the deep and the floodgates of the heavens had been closed, and the rain had stopped falling from the sky. 3 The water receded steadily from the earth.

— From The Book of Genesis, The Bible, New International Version, 7:17-8:3.

💧 💧 💧

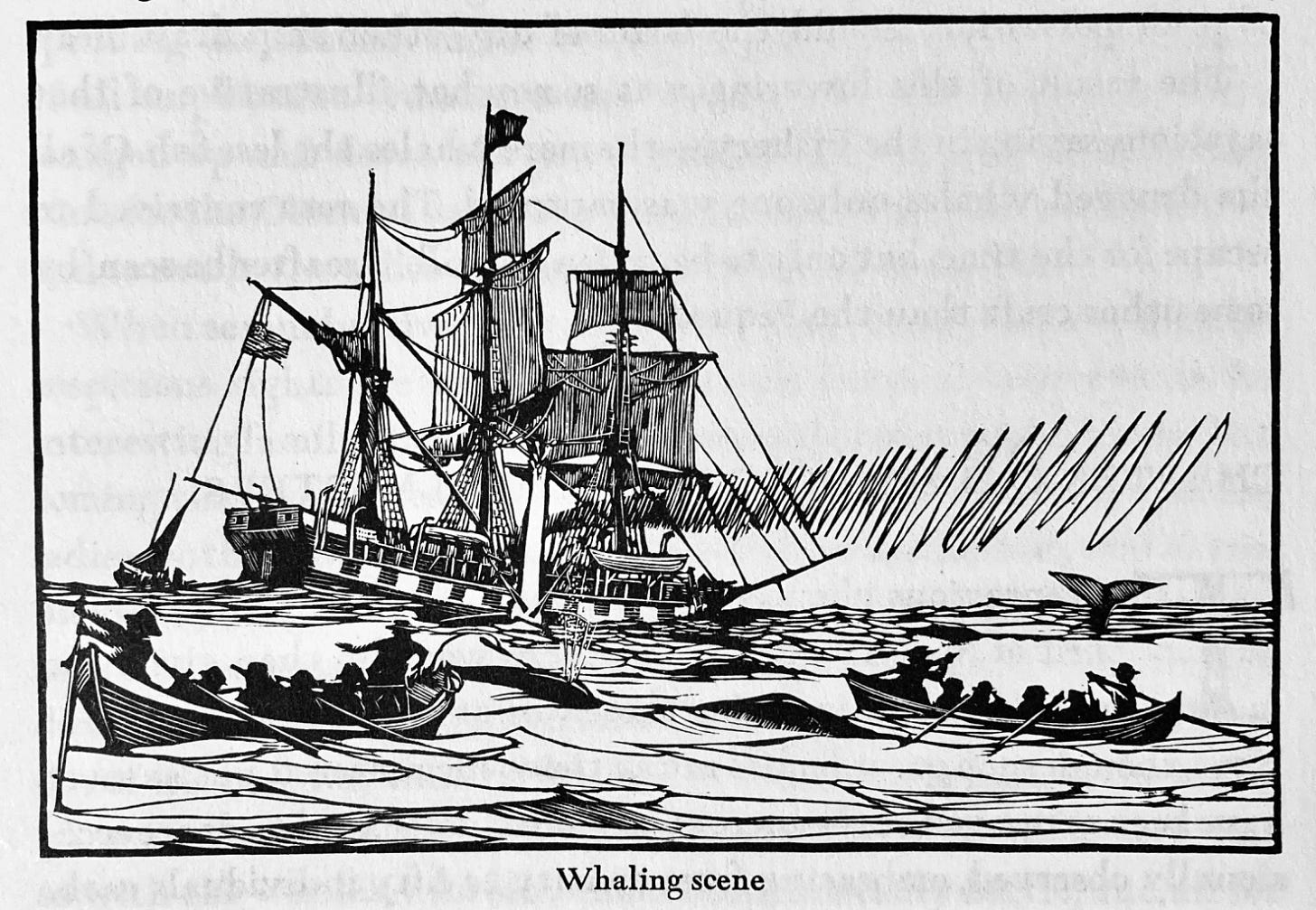

Moby-Dick

In the serene weather of the tropics it is exceedingly pleasant [on] the masthead; nay, to a dreamy meditative man it is delightful. There you stand, a hundred feet above the silent decks, striding along the deep, as if the masts were gigantic stilts, while beneath you and between your legs, as it were, swim the hugest monsters of the sea, even as ships once sailed between the boots of the famous Colossus at old Rhodes. There you stand, lost in the infinite series of the sea, with nothing ruffled but the waves. The tranced ship indolently rolls; the drowsy trade winds blow; everything resolves you into languor. For the most part, in this tropic whaling life, a sublime uneventfulness invests you.

— Herman Melville, “The Mast Head,” Moby-Dick

💧 💧 💧

Let’s Close with a Poem

Ask Me

Some time when the river is ice ask me

mistakes I have made. Ask me whether

what I have done is my life. Others

have come in their slow way into

my thought, and some have tried to help

or to hurt: ask me what difference

their strongest love or hate has made.

I will listen to what you say.

You and I can turn and look

at the silent river and wait. We know

the current is there, hidden; and there

are comings and goings from miles away

that hold the stillness exactly before us.

What the river says, that is what I say.

— William Stafford

💧 💧 💧

Do you need a poem to carry in your blood? Maybe something about rain or weather? Check out numerous suggested poems and see the guidelines for a community memorization and recitation project at this post. Join us Oct. 25 in sharing your poem on Substack!

It is sobering how well "Refuge" has held up as an anthem for our times. Both the illness and the vanishing habitat themes resonate perhaps even more deeply now than they did upon its publication. One of the loveliest braided memoirs I've ever read.

Everything here, marvelous, but especially putting up Stafford and Melville. I'm often surprised by literary writers I know who haven't read _Moby Dick_. The storms: Wowza, we so need a president in the US who understands the power of these recent storms to global warming. Yours is one of my favorite Substacks. I'll be writing you to you today to write again for Inner Life, this time as my guest and I'll promote you for the week before. Look for my email, lovely.