She Didn't Mean to Write a Bestseller - or to Change American Minds

And this women's rights advocate definitely didn't set out to be funny.

In 1872, agents of the American Publishing Company were busy promoting Mark Twain’s second book of humorous travels, Roughing It, when a packet arrived at Hartford headquarters. A newspaper poet and story-writer from upstate New York, north of Syracuse, wondered if publisher Elisha Bliss would be interested in a book manuscript from her. She enclosed samples of her poetry and prose.

The entrepreneurial Bliss, ever watchful for a potential blockbuster, thumbed over the pages “in good English,” as the author later recalled. But the dialect sketch of misspellings and malapropisms written in a voice the author called “Josiah Allen’s wife”— — now that had potential. Bliss wrote the author that yes, he would like to see a book from her in the voice of her character Samantha Allen.1

The author balked, perhaps wondering why she had sent the dialect sample in the first place. She asked Bliss to reconsider. She thought her poetry was her best work. Who would read a book about women’s rights from a comical, fictional country wife?

Finding the publisher firm in his judgment, Marietta Holley (1836-1926) accepted the assignment to write a full-length manuscript in the voice of her quirky character, Samantha. If the book paid, Holley would be able to afford comforts for her mother. Then again, how could such a thing pay?

Bliss encouraged his new author with letters and visits to her family home near the east end of Lake Ontario. Slowly, a book took shape in the form of comic episodes contrasting the common sense of farm wife Samantha Allen with the eagerness of her neighbor Betsey Babbet to find a husband. While Josiah Allen’s wife thought women should enjoy the rights of “common humanity,” Betsey tried to conform to the ideas of men, and therefore “professed herself willing to not have any rights at all,” as Holley wrote later of her first book’s main characters.2 For its satire of anti-suffrage arguments, the author titled the book A Beacon Light.

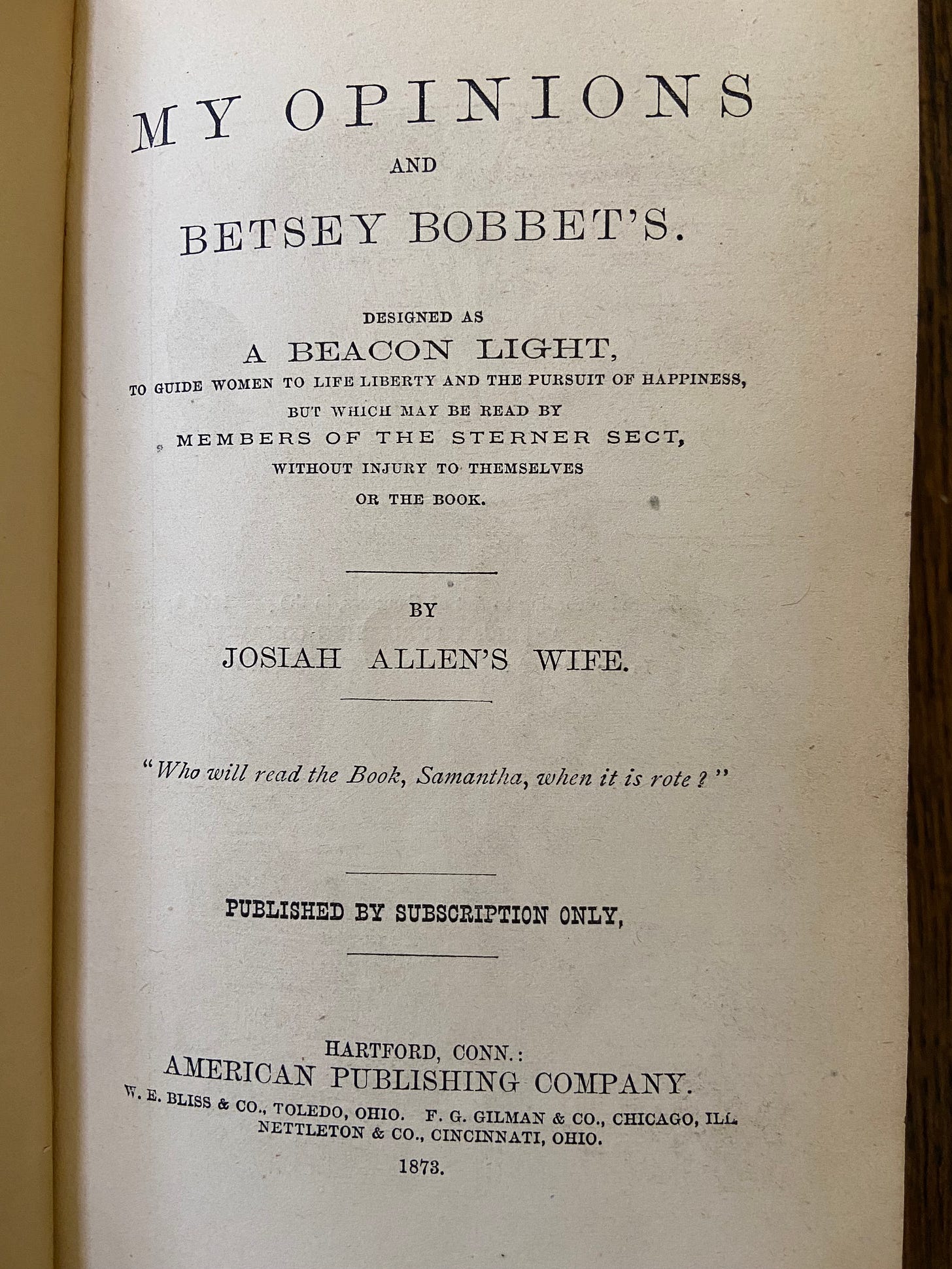

No, no, interjected Bliss once again. My Opinions and Betsey Babbet’s was a better title, he suggested, more likely to interest a wide audience. Author and publisher compromised, a vowel changed, and the book appeared in 1873 under the title:

My Opinions and Betsey Bobbet’s.

Designed as a BEACON LIGHT, to Guide Women to Life Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness, But Which May Be Read by Members of the Sterner Sect, without Injury to Themselves or the Book.

By Josiah Allen’s Wife.3

The name of the author, Marietta Holley, did not appear anywhere on the book.

Samantha’s Heyday (and Payday)

Elisha Bliss was right.

The domestic-political comedy was a hit.4 In a doctoral thesis on Holley, Joan Harkin LaCosse observed, “The acclaim and popularity of My Opinions was widespread and Holley was continually surprised by the reactions and the comments she received from those who had read the book” (p. 18). Pious Christians appreciated the book as much as the Bible. Readers asked how an unmarried writer knew so much about men. Holley’s character names — Samantha, Josiah, and Betsey — entered the cultural vocabulary as character types. (Holley later explained that people would tell her they had “a perfect Josiah or Samantha living near us” [LaCosse, p. 18]).

For the next forty years, Samantha Allen was the central figure of popular magazine stories and two dozen novels, such as My Wayward Pardner (1880), Samantha at the World’s Fair (1893), Samantha in Europe (1895), and Samantha on the Woman Question (1913) (epigraph: “Wimmen is my theme, and also Josiah”). Readers continued to respond to the practical wisdom of Samantha, surrounded by the folly of a world (and sometimes a husband) gone mad for fads, pieties, and amusements.

From the first royalty check of $600 in 1873 to the earnings that enabled her to build a large new house on the family property in 1888, Samantha and Josiah Allen made for Marietta Holley a comfortable living.5

What is most remarkable is the way Holley managed to take a progressive stance on controversial and divisive issues of her day — “the woman question,” “the race question,” temperance, child labor, patriotism in an imperial era, the growth of the tourism industry, the role of women in religious institutions, and more — while appealing to a large audience.

She published two dozen books from Josiah Allen’s Wife before the Nineteenth Amendment was passed in 1920. Historians have called her a “female Mark Twain” for her dialect humor and regional characters, but only recently has she been recognized as an original artist whose humor was uncommonly progressive.6 In an age that made suffragettes and female activists the butt of easy jokes, Samantha Allen made suffrage and legal rights for women feel like plain decency — while she cooked her husband’s favorite meals and mended his socks and otherwise showed that strong-minded women, given the vote, would not upset the social order too much.

Samantha on Marriage

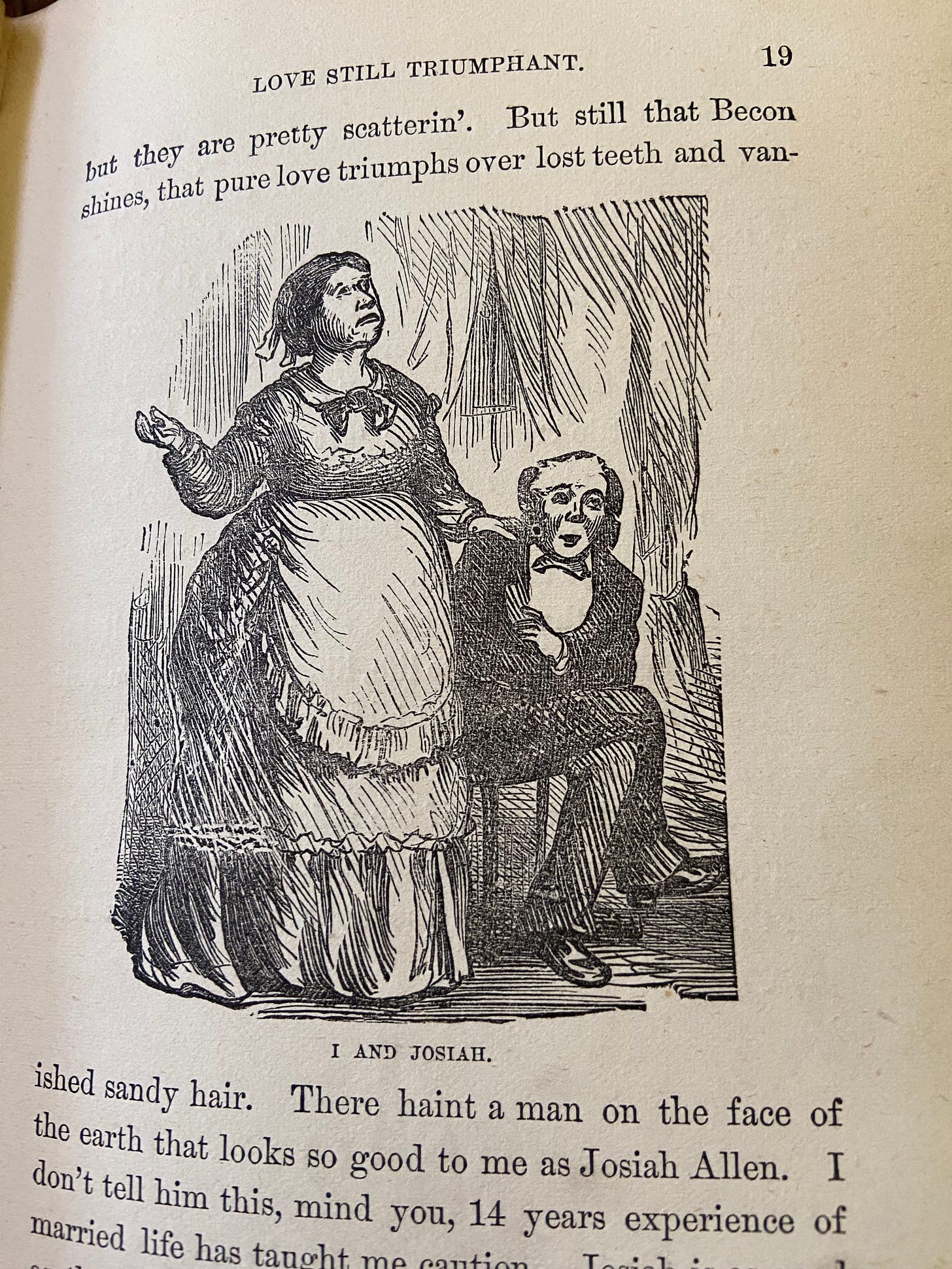

Key to Samantha’s wide American influence was her humorous portrayal of unromantic, average domesticity. “If anybody had told me when I was first born that I would marry to a widower, I should have been mad at ‘em,” begins My Opinions and Betsey Bobbet’s (p. 17), establishing that Samantha Allen has no more romance in her marriage than any other rural wife. But Samantha professes love for her spouse all the same, and “pure love,” she maintains, “triumphs over lost teeth and vanished sandy hair” (p. 19).

What unmarried Betsey Bobbet believes of marriage and what Samantha experiences are quite different. Josiah and Samantha vex each other in small ways almost continuously. In the Preface to My Wayward Pardner, Samantha announces a plan to write another book. “I told Josiah that I guessed I would write a book about several things — and wimmen,” she confides to the reader. “ ‘Let ‘em write about it themselves,’ ” answers the honored spouse, with his usual attitude toward her writing.

Pure love, as Samantha understands it, does not require a woman to make herself more agreeable to a man than he makes himself to her. To Betsey, she explains, “Of course men have to be corrected. I correct Josiah frequently, but I believe in doin’ it all up at one time and then have it over with, jest like a smart dash of a thunder shower that clears up the air.” On the other hand, with a southern accent, Betsey replies, “Oh, how a female woman that is blest with a deah companion, can even speak of correcting him, is a mystery to me” (p. 132). The two agree to disagree about whether a woman should always have a “sweet smile” for her “deah companion” (p. 130).

Samantha does not “believe in twittin’ all the time, about anything, for it makes anybody feel as unpleasant as it does to set down on a paper of carpet tacks” (p. 127). But when Josiah grumbles, “I wish you wouldn’t be so aggravatin’, Samantha,” the feeling is usually mutual (p. 127).

Samantha on Wimmin’s Spear

Josiah Allen’s wife not only provides a view of low-grade marital discord uncommon in the literature of the late nineteenth century; she also expresses clear views in favor of greater legal rights for women, including suffrage. At the time, such opinions were expected of radicals and the new college women, but not of plain-spoken rural wives like Samantha Allen. Marietta Holley’s contribution to the suffrage movement was to allow Americans to hear progressive political principles spoken in a rural vernacular. At no time was Samantha so sure to correct Josiah as when he uttered conventional platitudes about keeping women in their domestic “spear [sphere].”

A lecture on women’s rights offers an occasion for Josiah and Samantha to express their differing views on the central subject of My Opinions and Betsey Bobbet’s. Josiah begins, “Wimmin’s rights, wimmin’s rights. … I am sick of wimmin’s rights, I don’t believe in ‘em” (p. 85). Despite Samantha’s protestations, he maintains his ground that “poles and ‘lection boxes” are “too wearin for the fair sect.” This argument outrages Samantha, who exposes its ill logic:

“Josiah Allen,” says I, “you think that for a woman to stand up straight on her feet, under a blazin’ sun, and lift both her arms above her head, and pick seven bushels of hops, mingled with worms and spiders, into a gigantic box, day in, and day out, is awful healthy, so strengthenin’ and stimulatin’ to wimmin, but when it comes to droppin’ a little slip of clean paper into a small seven by nine box, once a year in a shady room, you are afraid it is goin’ to break down a woman’s constitution to once.”

She continues with rising dignity,

“You may go into any neighborhood you please, and if there is a family in it, where the wife has to set up leeches, make soap, cut her own kindlin’ wood, build fires in the winter, set up stove-pipes, dround kittens, hang out clothes lines, cord beds, cut up pork, skin calves, and hatchel flax with a baby lashed to her side—I haint afraid to bet you a ten cent bill, that that womans husband thinks that wimmin are too feeble and delicate to go to the pole.” (My Opinions, pp. 92-93. For “pole,” think “polling place.”)

Marietta Holley knew Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. She received invitations to speak at public events, which she declined. She preferred to make her contribution to the women’s movement from her home. She was aware that pro-suffrage views were “decidedly unpopular” and that they stood a better chance if conveyed by a character “meekly claiming to be the wife of Josiah Allen, and so stand[ing] in the shadow of a man’s personality” (Holley quoted in LaCasse, p. 17). Furthermore, the structure of her first books presented “two sides of the question” of women’s rights, one represented by Samantha, the other by Betsey Bobbet (LaCasse, p. 17).

According to the Encyclopedia of American Humorists,

Holley’s persona used humor for a new end: it made accessible and palatable the ideals of the temperance and suffrage movements . . . . Whereas the earlier comedians had made the woman, particularly the woman’s rights advocate, the butt of their comedy, Holley created characters of both genders who embodied the absurdities of intemperance and antisuffrage.7

Holley did not wear out her welcome with readers by belaboring a single point. She made Samantha a curious traveler of the world — the opposite of her own homebody preferences — and in subsequent volumes demonstrated Samantha’s good sense in countless comical scenarios — taking boarders, vacationing with fashionable people, rebuffing surprise visitors, and more. Through all the volumes, Samantha demonstrated a married woman’s capacity to manage affairs at least as well as her husband.

A Poet First

As for Marietta Holley, she never married. Whether this was because her generation lost so many men to the Civil War or because she had seen enough of other people’s marriages to keep herself out of such trouble is not clear.

What is most ironic is that Holley wished to be known as a poet, not a social crusader or humorist. For a taste of her poetry, visit

by who has reprinted three of her poems (indexed here).When she died in 1926 at age 89, after the Nineteenth Amendment gave U.S. women the right to vote, the brand of vernacular humor that Elisha Bliss had encouraged half a century earlier was no longer fashionable. (For reference, Ernest Hemingway published The Sun Also Rises in 1926.)

I can’t help but wonder what Marietta Holley might write today to disarm the country with laughter and practical sense.

Writers are not always the best judges of their own work. Is there a Marietta Holley today mistaking her/his/their vocation who could speak plain sense in a modern heartland vernacular?

Imagine how a satirist with Holley’s tact might crack words like a thunder shower and clear the discordant air of democracy — between now and November!

Sample Titles by Marietta Holley:

My Opinions and Betsey Bobbet’s (1873)

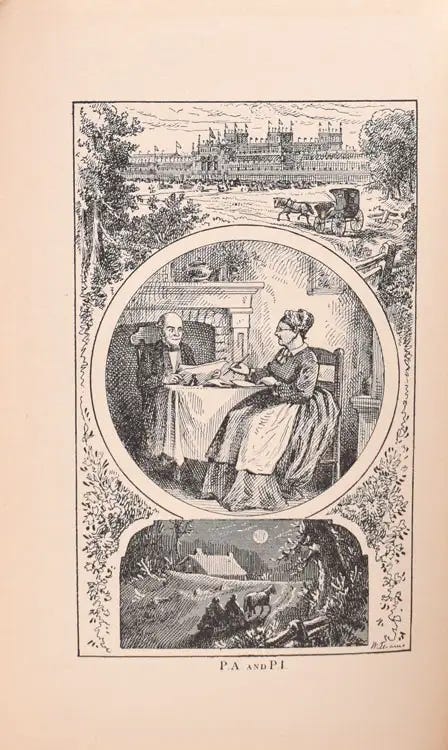

Josiah Allen’s Wife as a P.A. and P.I., Samantha at the Centennial (1877)

My Wayward Pardner; or, My Trials with Josiah, America, the Widow Bump, and Etcetery (1880)

Sweet Cicely: Josiah Allen as a Politician (1885)

Samantha at Saratoga, or Flirtin’ with Fashion (1887)

Samantha on the Race Problem (1892)

Samantha among the Brethren (1892)

Samantha at the World’s Fair (1893)

Samantha in Europe (1895)

Samantha at the St. Louis Exposition (1904)

Samantha on Children’s Rights (1906)

Samantha vs. Josiah, Being the Story of the Borrowed Automobile and What Became of It (1906)

Samantha on the Woman Question (1913)

Josiah Allen on the Woman Question (1914)

Samantha Rastles the Woman Question, A collection edited by Jane Curry (1983)

Joan Harkin LaCosse, Marietta Holley on Temperance and Women’s Rights: Framing and Interpreting a Legacy of Social Reform. Doctoral Thesis, Georgetown University, 2016, p. 16. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/1040736/LaCoss_georgetown_0076D_13162.pdf?sequence=1

LaCosse, p. 17.

Kate H. Winter, Marietta Holley: Life with “Josiah Allen’s Wife” (Syracuse University Press, 2005), p. 44.

LaCosse, p. 17.

Kate Winter, p. 45; Roxie Holmstead, “Marietta Holley, 1836-192[6],” History’s Women: The Unsung Heroines, https://historyswomen.com/the-arts/marietta-holley/.

Born in July 1836, Marietta Holley was only 7 1/2 months younger than Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain). She was one month older than another contemporary humorist, Bret Harte.

Stephen H. Gale, editor, Encyclopedia of American Humorists (Taylor & Francis, 2016), p. 225.

This is fascinating, Tara! I'd never heard of Marietta Holley before.

Love the passage listing all of the rigorous work that women do while being thought too "feeble" for the vote. Echoes of Franklin's "The Speech of Polly Baker"? If I ever return to my Am Lit series, Franklin's short fiction will get a nod.

You're also making me think of the late Patrick McManus, an outdoor humorist who I read aloud to my daughters (while squinting at some very outdated gender tropes). He was a favorite of my grandmother's, also the most resilient person I've ever known, also a homemaker who could have been an executive.