People Still Buy Their Books

These two inspirational writers made markets where none existed

It was a relief to learn over the past week that Americans continue to buy printed books upwards of the hundreds of millions. The information came in a flurry of responses to a viral post with a provocative if misleading title, “No one buys books.” In short, according to those who know how to read the data, people do buy books, though the business model of publishing is changing, and it continues to be difficult to make a living as an author.1

Even more reassurance comes from the long view of a literary historian. The technologies and business models of art and writing change at least every century or two, if not more often.2 Nothing is wrong or broken about the expectation that business models and technologies for publishing will change again, although the printed book has proven exceptionally durable and adaptable as a form, making it unlikely to be replaced soon.

We are not helpless pawns in a system of someone else’s making. Given the benefit of hindsight, we can see which small, unlikely actions in literature have produced powerful, unexpected effects. Taking the long view reminds us that careers are made from small acts, crazy ideas, and guesses. No market conditions have ever put writers (or publishers) at their ease.

I am reminded of two early American literary figures, one a writer, the other a publisher. Both have exercised incalculable influence on American literature. Although they were white and male and therefore had more opportunities and fewer obstructions than Fanny Fern or Ida B. Wells, still, neither had any reason to expect the success he found, or any premonition of it when he was “poor as a rat,” with no obvious way to make a living from his taste for language, verse, and story.

The publishing scene has never remained both stable and promising for long, but some daring ones have managed to make their own markets where none existed before. I find inspiration in their stories.

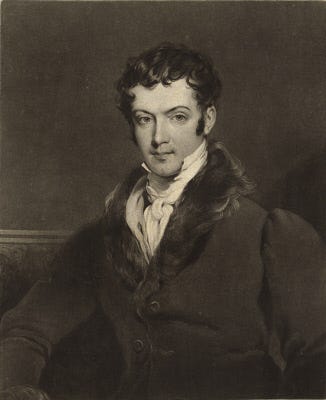

How the Man Unfitted to Labor Advanced the American Short Story

When Washington Irving wrote his famous “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” tales, the short story was not yet a named genre. These supernatural fictions appeared in a collection originally issued in seven installments, called The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (1819-20), surrounded by works just as short but lacking in plot. To early nineteenth-century readers, the “sketch” was a genre common among travelers who wanted to create a quick picture with language. In a few paragraphs or several pages, authors described a character, a scene, a city, or a region and its folk. Sketches were relatively static, full of detail and style but scant in conflict or activity.

Into The Sketch Book Irving snuck a few oddball tales in order to “sketch” or exemplify the superstitions of the old Dutch settlers of the Hudson River. The point was not to invent a genre of short fiction grounded in conflict and change; rather, conflict and change were part of the experience of the previous American generations. To sketch the character of the people seemed to require a retelling of tales they may have told. (No matter that Irving got his ideas reading German romantic literature. A good story is a good story!)

You wouldn’t have expected such an idle fellow as the youngest Irving to help create a whole new genre! That’s a job for someone of more ambition, right?

As the frail youngest child in a family of eleven children, Washington Irving was, by one old-fashioned account, “a bit spoiled”: “His brothers sacrificed for him, idolized him” (Pattee 4). That is to say, they made him a shareholder in the family business without requiring much work. For his health, the family sent him traveling. When offered an editorial job, he declined on the grounds of his “desultory” upbringing, which made him — as he explained to the patron who offered employment — “unfitted for any periodically recurring task, or any stipulated labor of body or mind” (Pattee 5).3 When the family business failed and one of his brothers arranged a job for him as a clerk, Irving refused so he could write. “I now wish to be left for a little while entirely to the bent of my own inclination, and not agitated by new plans for subsistence,” he replied to the family that provided his subsistence (Jones 176).45

Much later, Irving described himself at that time as “poor as a rat” but happy to live so much in his imagination, his labor consisting of learning the German language so he could read the new romances.6

In Irving’s day, the precursors to short stories were moral tales in newspapers, longer sketches, or unfinished novels. There was no market for short stories until he created one. His Sketch Book proved to be so popular that after it, “sketches and tales became the literary fashion in America, and in such volume did they come that vehicles for their dissemination became imperative.” Magazines and annual gift books proliferated in the 1830s and ‘40s, “nurseries for the short story” that emerged “indirectly” from Irving’s success (Pattee 20-21).

Incidentally, after the Sketch Book, Irving was considerably less idle, taking one literary assignment after another, often involving research or travel. To pay for the home he bought along the Hudson River, he kept writing for newspapers. His reputation as a man of leisure reflects his preference and taste, but as a writer who needed to pay the bills, Irving worked as much as anyone.

Just because you invent a genre doesn’t mean it’s all private jets and bon-bons after that.

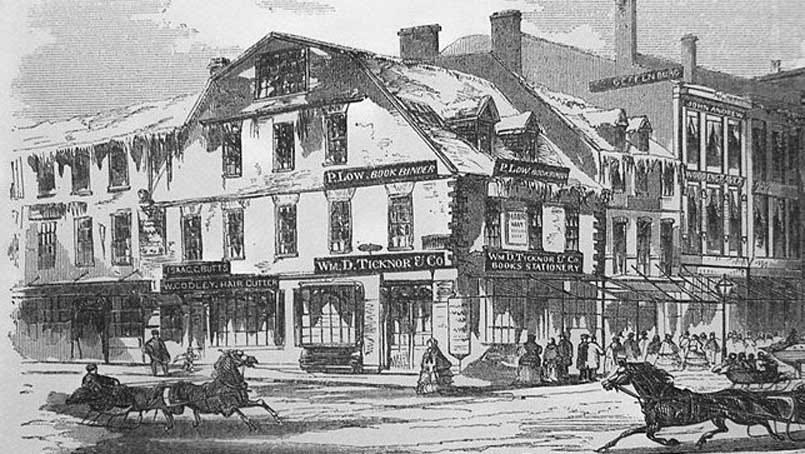

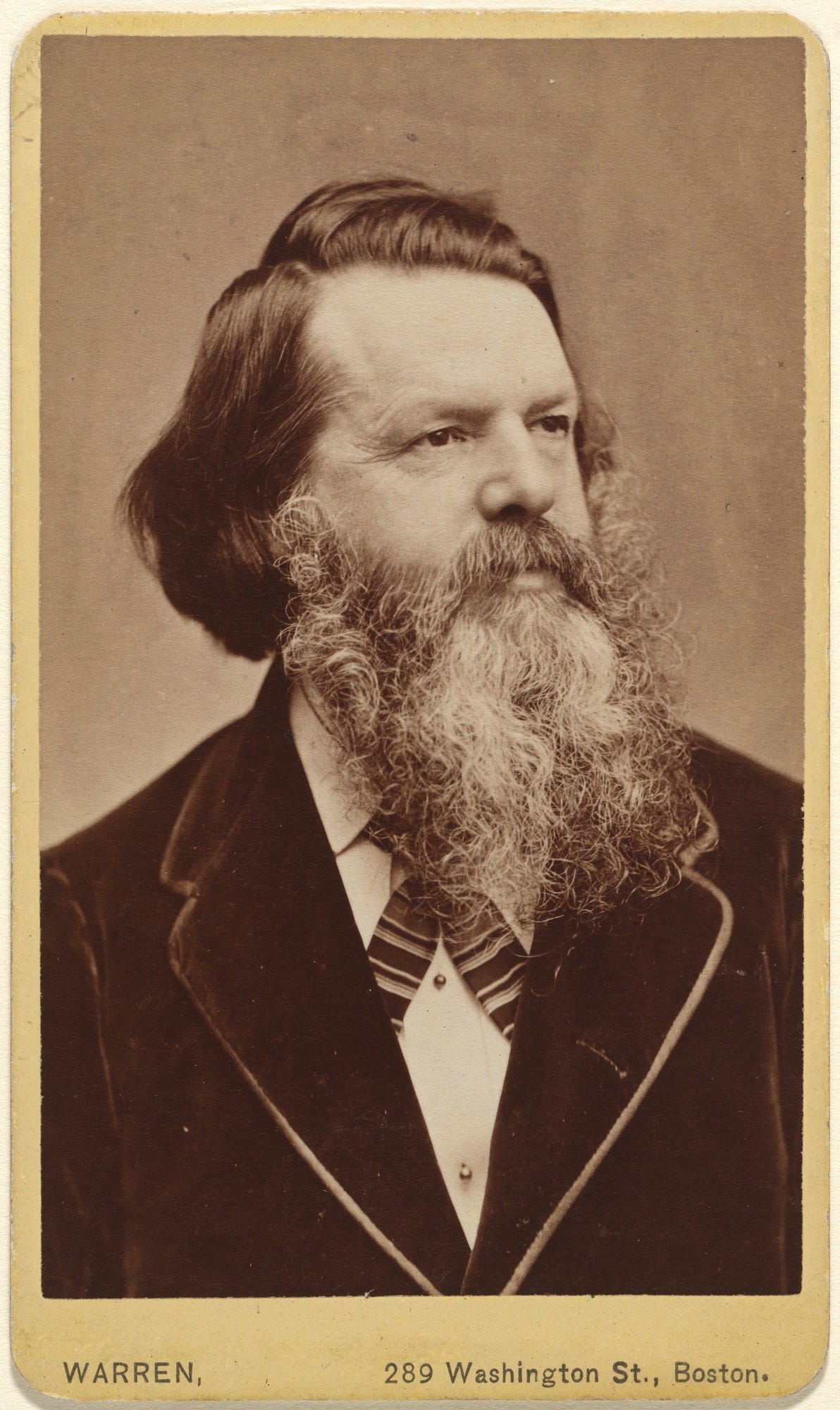

From Bookstore Apprentice and Minor Poet to Publisher of the American Literary Canon

Irving was approaching fifty and just back in the U.S. after seventeen years in Europe when a fourteen-year-old boy from New Hampshire went to work as an apprentice at a bookstore in Boston. He learned every aspect of the business and wrote poetry on the side. A memoir published after his death told the story of a gift that the youth, James, discovered during this period, a source of amusement to fellow apprentices. According to the story, he could predict what book a person would buy soon after they entered the shop.7 If true, it would have been the least of the qualities that caused his next employer to take James as a junior partner at age 21. He was said to have a head for business and for literature.

James also had a magnetism that others admired. During his years as a clerk, his friends converged on his boarding house after work hours for “glorious hilarity.” James was “never dull, never morose, never desponding. Full of cheer himself, he radiated cheer into us.” According to one of these early friends, James “from the start had deliberately formed in his mind an ideal of a publisher who might profit by men of letters, and at the same time make men of letters profit by him” (Derby, pp. 621-22; emphasis added).

The bookstore where James had come to work was also a printing shop, known for “Scientific, Educational, Religious, Medical and Juvenile books” — all categories that paid a publisher in those days as in ours — but not much that was considered at the time “belles-lettres” (Derby, p. 616). In those days, as in ours, poetry didn’t pay. James was unique in believing that it should and could.

After James became an unnamed junior partner of the bookselling and publishing company in 1839, the firm began to show new literary interests. The first step was to secure an international list of prominent authors. Dickens, Tennyson, and other English writers signed with the Boston firm as their official American publisher. What’s notable about this is that there was no international copyright at the time, so American and British presses were accustomed to printing unauthorized editions of the other country’s best authors for free — a 100% profitable scheme. The royalties that James and his senior partner offered to British authors were a savvy move to establish relations of trust and goodwill with the most noteworthy names in literature. All of this elevated the brand of Ticknor & Fields and the status of the American writers who signed with the firm.

The firm of Ticknor & Fields represented an exceptionally successful partnership in literary history, with William Ticknor’s head for business and James T. Field’s literary taste, affability, and confidence that literature could pay. The firm offered beautiful editions on quality paper, advertised extensively (before advertising agencies developed practices that were widely adopted later), and treated authors like celebrities, based on Fields’s conviction that literature had cultural value.8

The firm became noteworthy for unusually high royalties. James Fields was known as “the author’s friend, the poet publisher” (Derby, p. 619). William Ticknor was an intimate friend of Nathaniel Hawthorne before Hawthorne’s name became synonymous with American literature. Shy Hawthorne trusted Fields’s literary judgment and credited him with his high literary reputation.

The Old Corner Bookstore in Boston where James Fields apprenticed at age 14, where he became a junior partner at age 21, and which he sold after Ticknor’s death in 1864, was a beloved gathering place for New England literati and is preserved as an historic site (and occupied commercially) today.

In the 1876 U.S. centennial fair in Philadelphia, the Ticknor & Fields display represented what would become for the next century the foundation of a syllabus of American literature — Emerson, Longfellow, Holmes, Whittier, Lowell, Hawthorne, Thoreau, Stowe, Harte, Twain, and so on. (After 1876, the firm would add Charles Chesnutt, Sarah Orne Jewett, and others who are read today.)

If they had asked, both Washington Irving and James Fields would have heard advice like, “Well, you can’t make a living at that!”

They didn’t ask.

This post thinks it is the first of two parts. Coming up: Are there any signs of people creating genres or making markets from today’s digital technologies?

Here’s a more detailed overview of the most helpful articles I’ve seen on this subject. All are recommended if the state of publishing interests you.

demonstrates why 1 billion books a year is a conservative estimate of American book buying in “Yes, People Do Buy Books.”Indie publisher

of She Writes Press and SparkPress explains how small presses can be profitable from modest book sales in “People Buy Books, Publishing Is Thriving, and Substack Will Never Replace Books.”In a letter to clients prior to the viral post, book coach and consultant

described “Shifting Ground in the Publishing Landscape,” especially the growth of subsidy publishing, in which authors share the cost of publishing for a higher share of the revenues.At the request of her readers,

also demystified the book industry with a survey of facts at her publishing newsletter, The Hot Sheet.Based on her experience as a successful midlist fantasy novelist,

explains why even though the publishing system is flawed and most writers cannot make a living from it, writing appeals to other values. “The midlist,” she argues, “is full of writers with small to medium-sized followings, working hard and building careers and following their dreams” (“Beyond Bestsellers: Yes, People Still Buy Books”).Thanks to

for drawing my attention to some of these articles in his essay “Do Books Make Money?” also provides excellent, lucid illustrations of how a publisher’s expectations about a book, the print run, and sales after the first year create many different versions of “success” for a book. (“A Different Way to Look at Book Sales”).Finally, if you’ve followed this discussion at all and have missed

’s satiric treatment of it, you can fix that right now and be happier for it (“Yes, Substack Really Will Replace the Book Publishing Industry”).If anyone reading this has been paid to produce a papyrus scroll or to sing a long, flattering poem to amuse aristocrats, please let me know. Maybe business models don’t change as often as I think.

Fred Lewis Pattee, The Development of the American Short Story, 1923. Biblo and Tannen, 1966.

Brian Jay Jones, Washington Irving: An American Original. Arcade, 2008.

Raise your hand if you’d love to not be agitated by new plans for subsistence!

Richard D. Rust, et al., eds., The Complete Works of Washington Irving, 30 vols. Twayne, 1986. Volume 25, p. 751.

J. C. Derby, “James T. Fields,” Fifty Years among Authors, Books and Publishers. G. W. Carleton & Co., 1884, p. 621. This skill might be a holy grail of booksellers. The novelist and bookstore owner Louise Erdrich created a character with the same ability, the protagonist of her novel The Sentence (2021).

See Michael Winship, American Literary Publishing in the Mid-Nineteenth Century: The Business of Ticknor and Fields. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Tara, again you filled in crucial gaps in my knowledge in your usual delightful way.

I have loved some of my reading experiences on Substack including reading serializations and being able to talk to the author. I think many people would pay a premium for that experience. Hard to scale though.

And I nominate your Washington Irving quote as the best Resume header ever:

"[I am] unfitted for any periodically recurring task, or any stipulated labor of body or mind”

People do buy books all the time. I saw that provocative title and rolled my eyes. Well said response Tara!