The Century Plant and the Crusader

Tales of the long and short beginning

This post continues a series of author biographies from the past that shed light on writing today. Previous posts explored the pros and cons of a “niche” or business plan. Today’s article compares the different writing paths of one woman who found a mission early and another who found professional work first and a passion project later. At the risk of oversimplifying complex lives, I call them the crusader and the century plant. You may find there is a grain of truth in this comparison for anyone, writer or not.

In 2008, during the Great Recession, a writer lost her job. She had worked in advertising and marketing, media, and event planning, “Always writing — for someone else.”1 That same year, a scholarly biography of her great-grandmother was published. The communications professional, in her forties, decided it was time to write about her family.

Her great-grandmother had found her passion and mission at a younger age.

On May 4, 1884, Ida was reading a newspaper in the ladies’ car of a train when a conductor asked her to move. It was not the first time she had been asked to give up her seat for the ride between Memphis and the school where she worked as a teacher ten miles outside of town. Another time, the conductor had tried to remove her by force, and she had bitten his hand.

This time, she got off the train and went to a lawyer’s office.2

On Christmas Eve, she won a $500 judgment for discrimination against the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwestern Railroad because the segregated car where she had been directed to ride was not equal to the ladies’ car she had chosen. Black passengers were expected to ride in the smoking car, but the court agreed it was not an equal place to the ladies’ car for a petite twenty-one-year-old woman traveling to and from work.

The railroad appealed the case and prevailed in the state Supreme Court. Two years after the original decision, the Tennessee appellate judges affirmed the railroad’s right to send a Black woman to the “colored” car. To make matters worse, they judged the case a nuisance suit and ordered Ida to pay $200 — four months of her teacher’s pay.3

The incident shook Ida’s faith that U.S. laws would protect her. It fueled her passion for writing about racial injustice. Previously, she had belonged to a literary club. Now, under the pseudonym Iola, she wrote bold articles about her railroad case and other social grievances. Her articles were copied and her fame began to grow.

What motivated Ida was not only the insult she experienced on the train but the rolling back of rights for Black Americans just when her generation was getting on its feet. Like her parents, Ida had been born into slavery, in 1862. After the Civil War, James and Elizabeth Wells continued to work for wages for the Mississippi builder who had previously enslaved them as a carpenter and a cook. Before they died of yellow fever within 24 hours of each other in 1878, James had been active in political organization and voting. He had often called upon his oldest daughter to read the newspapers aloud, and thus she learned that Black voters in some places outnumbered whites, and that Black men were getting elected to state and federal offices during the Reconstruction years of the 1870s.4

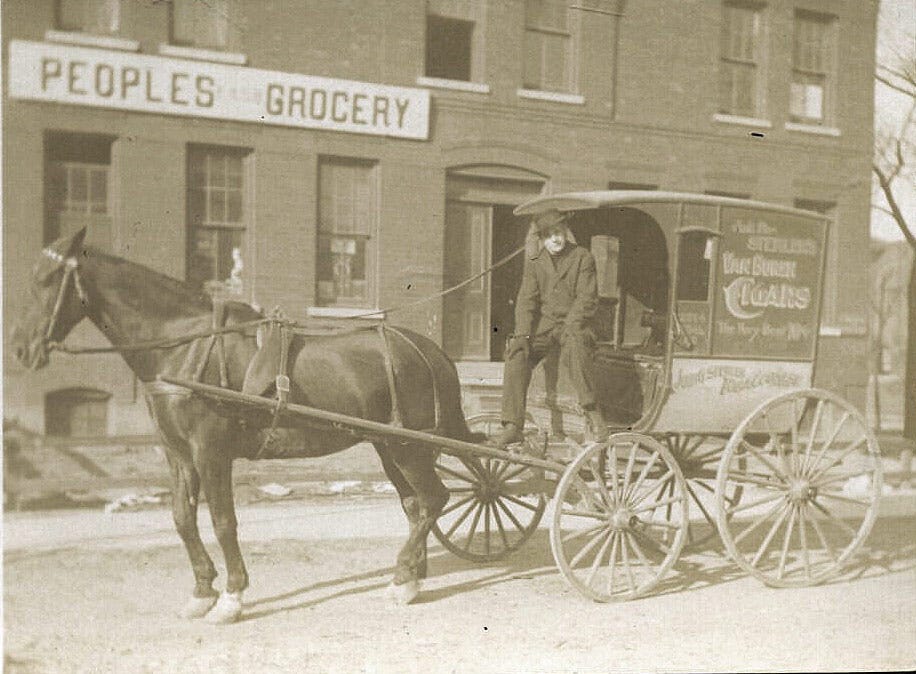

Growing up, she saw women like her mother going to school to learn to read. With some education herself until she became the primary provider for five younger siblings at the age of sixteen, she could work as a teacher. Later, in Memphis, she saw entrepreneurial Black men making a good living, like Tom Moss the postman and owner of a cooperative grocery store in a Black neighborhood of Memphis, called The People’s Grocery.

Finding that she had a taste and talent for journalism, Ida became part-owner of the Free Speech and Headlight, a Memphis paper founded by the pastor of the largest Black congregation in Tennessee, the Beale Street Baptist Church.5 The paper would help to amplify the voice of the activist, soon to be investigative journalist, Ida B. Wells.

In the spring of 1892, a few months before her thirtieth birthday, Ida Wells was out of state gathering subscriptions for the Free Speech when trouble broke out in Memphis. Her friend Tom Moss and two other majority shareholders of The People’s Grocery were arrested with others who tried to defend the store from an attack incited by the white owner of a rival store across the street. Before Wells made it back to Memphis, Tom Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart had been shot dead by white supremacists angry over the success of a Black-owned business.

She wrote in her autobiography, “This is what opened my eyes to what lynching really was. An excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized.”6 She began researching other lynching cases, many of them allegedly punishing Black men for the rape of white women. In May she wrote in the Free Speech, “nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern white men are not careful, they will over-reach themselves and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will have a very damaging effect on the moral reputation of their women.”7

She had written inflammatory criticism before, but this was considered “obscene.” On May 27, a mob attacked and burned the office of the Free Speech. Wells and her fellow editor had been warned and were out of town. Both received death threats. The increasingly well-known activist never set foot in Memphis again.

Angry at the murder of her friends and the loss of all she owned, by the time she turned thirty in July 1892, Miss Ida B. Wells had made it her mission to fight the white supremacists of Memphis and the terror of lynch law.

No one else was asking the questions she thought were important. She gathered statistics about lynching from newspapers. She interviewed survivors. In October 1892, the leading Black newspaper in New York City, the New York Age, published her research in a pamphlet titled Southern Horrors. Lynch Law in All Its Phases. A follow-up, The Red Record, added more data in 1895.

Between those two culminations of her investigative reporting, in 1893 and 1894, Wells traveled twice to Britain, where she was received warmly. As historians Linda Peavy and Ursula Smith have written,

She found audiences who listened, spellbound, to her accounts of lynch-mob brutality, newspapers that made those accounts available to the masses, and churches that agreed to censure their American counterparts that remained silent in the face of such injustice.

In Manchester, a journalist observed, “Her quiet, refined manner, her intelligence and earnestness, her avoidance of all oratorical tricks, and her dependence upon the simple eloquence of facts makes her a powerful and convincing advocate.”8

She was invited to address members of Parliament, who assured her that British people expected Black Southerners to receive fair trials.

Peavy and Smith attribute the end of lynching in Memphis in part to Wells’s sustained efforts. The same Memphis paper that called Wells’s slurs against Southern white women “obscene” complained after another Black man was lynched in the summer of 1893, “Already the press and pulpit of Britain are thundering against us, and Memphis has been held up to them as an illustration of barbarism and savagery.”

The person who was just at that time holding up Memphis as a flagrant example of lynching atrocity was, of course, Ida B. Wells.

A year later, after Wells’s second trip to England, the merchants of Memphis condemned a fresh act of white-on-Black violence, and in this case, thirteen white men were brought to trial for lynching six Black men. The tide of public sentiment was turning against such acts in the city where Wells herself had been threatened with murder for an offensive newspaper article just two years earlier.9

Still only thirty-two, Wells had plenty of steam left for activism and writing. It is worth mentioning a few highlights. In 1895, she married fellow writer and attorney Ferdinand Barnett, proprietor of a Black newspaper in Chicago. While raising four children and marching for women’s suffrage, she maintained the Negro Fellowship League Reading Room and Social Center in Chicago for a decade. As she explained, “Only one social center welcomes the Negro, and that is the saloon.” Until 1920, her library, lodging, and social center and her husband’s legal aid helped men find jobs and stay off the street when they relocated to Chicago from the South. When the center was at risk of closing, Wells-Barnett went to work as a probation officer to keep it open.10

Although racial terror did not end as a result of Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s activism, her writing helped to expose Southern lynching as an act of white supremacy aimed at keeping Black Americans from making social or economic progress after the end of slavery.

And her work had countless other effects. She helped to organize the NAACP, used her Jim Crow experience in the South to warn against segregation in Chicago schools, called out racial injustice in the federal government and the military, gave others the courage to join her in decrying the practice of lynching (including Jane Addams), and more. You might say Ida B. Wells found a mission in fighting lynching, and that would be true. But the breadth of her activism also indicates a larger mission to topple white male supremacy and shine a way forward for survivors.

In 2008, Ida Wells-Barnett’s great-granddaughter joined her ancestor’s work with a niche of her own, writing stories of Black women that spread hope and dignity. She came to the work about thirty years later in life than her predecessor.

In 1970s Chicago, the grandchildren of Ida and Ferdinand Barnett’s youngest daughter knew about their famous great-grandmother, “but felt no pressure to match Ida’s accomplishments. We were encouraged to develop our own interests and skills. … Ida lived her life. And I could live mine.”11 It was never a foregone conclusion that Michelle Duster would become a champion of the great-grandmother or her causes, even with their shared talent for writing. But thanks to her midlife interest in her ancestor and the stories of other Black women, the former communications professional now identifies as an “Author, Educator, and Public Historian.”12

Newsletter authors today break into writing at every stage of life: twenties, fifties, eighties, etc. The “Once and Future Author” series offers reminders from history that there is no single pattern of a writer’s career.

The writing life sometimes takes hold of a person like a crusade. And sometimes it grows like a century plant. There is good news in this metaphor. The agave americana or century plant does not really take one hundred years to bloom. It might take a decade or three, but when the spiny aloe does eventually bloom, no one begrudges it the time it took to sink roots in arid, inhospitable soil.13

On her twenty-fifth birthday (three months after her railroad suit was overturned), Ida Wells could say this much about her future: “I hunger & thirst after righteousness & knowledge.”14

A writer is accustomed to this hunger and thirst, and to the fast-slow ferment of creation that waits for a just-right moment to bloom.

Michelle Duster, Ida B. the Queen (Simon & Schuster, 2021), p. 14.

This story is told in Duster, Ida B., the Queen, pp. 38-43. For a full scholarly biography of Wells, see Paula J. Giddings, IDA: A Sword among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign Against Lynching (HarperCollins, Amistad, 2008).

You may be familiar with a later case that had an opposite trajectory. In 1955, Rosa Parks was fined by a Montgomery, Alabama, court for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white man when asked to do so, but the U.S. Supreme Court exonerated her a year later, weakening Jim Crow segregation laws and igniting the Civil Rights movement in the U.S.

Duster, pp. 57-64.

Duster, p. 51; Linda Peavey and Ursula Smith, “Ida B. Wells’ Determined Quest for Equality,” Memphis Magazine, April 9, 2019, https://memphismagazine.com/features/ida-b-wells-determined-quest-for-equality/. Adapted from their book Women Who Changed Things (Atheneum, 1983). (Hereafter, this article will be referred to as Peavy and Smith.)

Duster, p. 54.

Peavy and Smith.

Peavy and Smith.

Peavy and Smith.

Duster, p. 17-18.

Duster, p. 12.

From Michelle Duster’s website, https://mldwrites.com/.

The century plant metaphor may require a little stretch of imagination in this case. While Michelle Duster may have found a passion project in her ancestor’s life after twenty years of other professional work, her six books, numerous articles, and public history projects make it clear she is not waiting a decade between blooms.

Duster, p. 49.

Ida Wells was a truly remarkable woman.

Such an inspiring article, Tara.