Which Literary Début is True?

This classic author wouldn't overstate the story, would he?

Have you ever found yourself in the right place at the right time for something extraordinary? If so, how did you speak of it later?

(You wouldn’t — would you? — embellish?)

Welcome to Quiet Reading, a weekly refuge for our shared humanity, inspired by authors, books, and this world of marvels. In The Once and Future Author series, we dig in to the backstory of writers from the past for revelations about our common human condition. Essays in this series are structured to leave the identity of the subject in doubt until the end. Sources appear at the end of the essay.

In this edition, is it time to change the story about a turning point in a storied career?

Right place, right time

On June 15, 1866, a well-dressed Englishman and a rumpled American boarded a steamboat on the Big Island of Hawaii for the thirty-hour trip to Honolulu. A week earlier, they had set out together on horseback from Volcano House on Mount Kilauea, traveling down first to the rainy eastern coast of the island, then back across to the west side to catch the inter-island boat. The American, a journalist, could already feel the saddle sores that would soon erupt in painful boils. But the trip was worth it. He had walked the lava beds of an erupting volcano and watched the stars come out over the crater at night.

The same day that the travelers left the Big Island, back on the rainy coast where they had just passed, a longboat came ashore near a fishing village, carrying fifteen survivors from a ship that had burned at sea. The captain, two passengers, and twelve crew members had traveled four thousand miles in forty-three days since losing their vessel — on a four-day supply of fresh water and a ten-day supply of food.

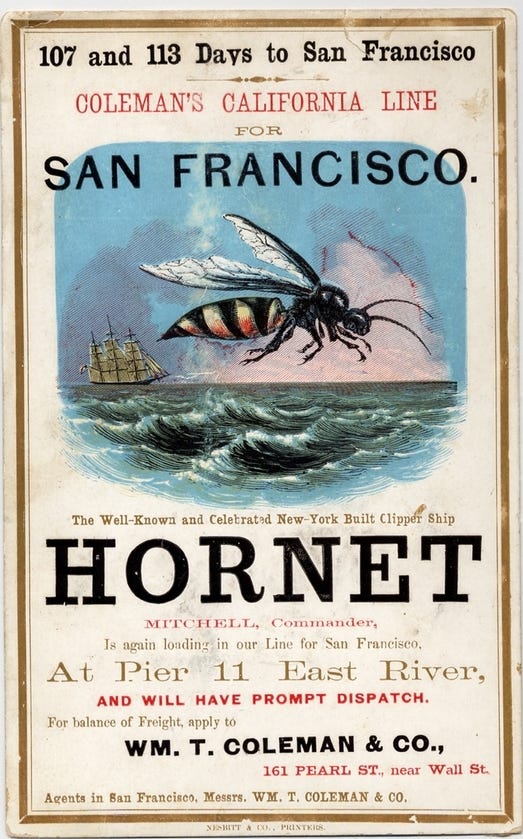

The American journalist was in bed in Honolulu, nursing his sores and writing letters, when news reached Oahu about the survivors of the clipper ship Hornet, bound from New York to San Francisco when their cargo of oil caught fire in the Pacific north of the equator. Their lives seemed miraculous. Smelling a big, career-making story, the journalist arranged to hear the details first-hand when the starved men came to recuperate at a Honolulu hospital.

Even better, a month later he shared a ship back to California with the captain of the Hornet and two passengers. From his hospital interviews, the American wrote a hasty story for his California employer, the Sacramento Union. From the private journals he read on the Pacific crossing, he prepared an article called “Forty-Three Days in an Open Boat.” Confident in his “scoop,” he “looked around for the best magazine to go up to glory in” and “selected the most important one in New York,” Harper’s Monthly. The prize story appeared in December. Who could doubt that his career was on its way?

The Scoop

Much later, the journalist would explain how his access to first-hand accounts of the Hornet disaster lifted his scrappy, provincial career to a new level. After meeting with the third mate and ten crew members in Honolulu, he determined to break the news to the mainland papers ahead of the competition. He remembered decades later,

I took no dinner, for there was no time to spare if I would beat the other correspondents. I spent four hours arranging the notes in their proper order, then wrote all night and beyond it; with this result: that I had a very long and detailed account of the “Hornet” episode ready at nine in the morning, while the other correspondents of the San Francisco journals had nothing but a brief outline report—for they didn’t sit up. The now-and-then schooner was to sail for San Francisco about nine; when I reached the dock she was free forward and was just casting off her stern-line. My fat envelope was thrown by a strong hand, and fell on board all right, and my victory was a safe thing.

To his mother, flushed with the story in 1866, he wrote,

If my account gets to the Sacramento Union first, it will be published first all over the United States, France, England, Russia and Germany — all over the world, I may say.

Indeed, historians unanimously accepted the journalist’s judgment about the importance of his “scoop.” According to one friend, his account was “the first news of the terrible misfortune,” at which “the whole reading world thrilled with pity.” Subsequently, another affirmed that the journalist’s story was “telegraphed everywhere.” And so on.

Although the journalist had worked for newspapers almost as long as he could spit, he called the Hornet article for Harper’s his “début as a literary person.” It made an exciting story.

Except it didn’t happen exactly the way he said.

*

A recent biographer, checking the facts of this period, found that the journalist had overstated the impact of his Hornet scoop. His was not the account heard ‘round the world. Other journalists also sent letters on the same ship that carried our friend’s “fat envelope.” The captain of the Hornet sent his shipping agent the names of his fellow survivors. Our ambitious journalist, it turns out, was “no more than a bit player in reporting the news to the nation and the world of the Hornet disaster and the near-miraculous survival of the men.”

Ouch.

But hold on. The Hornet story did give the knockabout journalist something important. It gave him a human story worthy of his pen. And it gave him his first serious hope that he would graduate from low-paying, provincial journalism.

The provincial journalist

Not long before he rode up and down Kilauea in a saddle, the journalist had written to his sister in the States in a “bitter” frame of mind. Despite the pleasures of Hawaii, he could not help but remember a family quarrel. If his older brother had consented to sell some family property, he would not be “drifting about on the outskirts of the world, battling for bread,” “in poverty & exile now.” For this, the young man complained, “I shall never entirely forgive him.”

Accustomed to coming up with any copy he could sell, the journalist knew the Hornet story was special. Captain Josiah Mitchell impressed him so much that he compared him with General Ulysses Grant. With this story, he could “go up to glory” as “a literary person.” No matter that Harper’s Monthly misspelled his name. The important result was the way the Hornet story boosted the young writer in his own eyes.

What Came After

Biographers generally agree that the journalist’s career entered a new phase when he got back to the mainland from Hawaii in 1866. They have given some credit to the Hornet article — which now we know to be erroneous; its influence was not as wide as the author imagined. And yet other things started to go right at the same time.

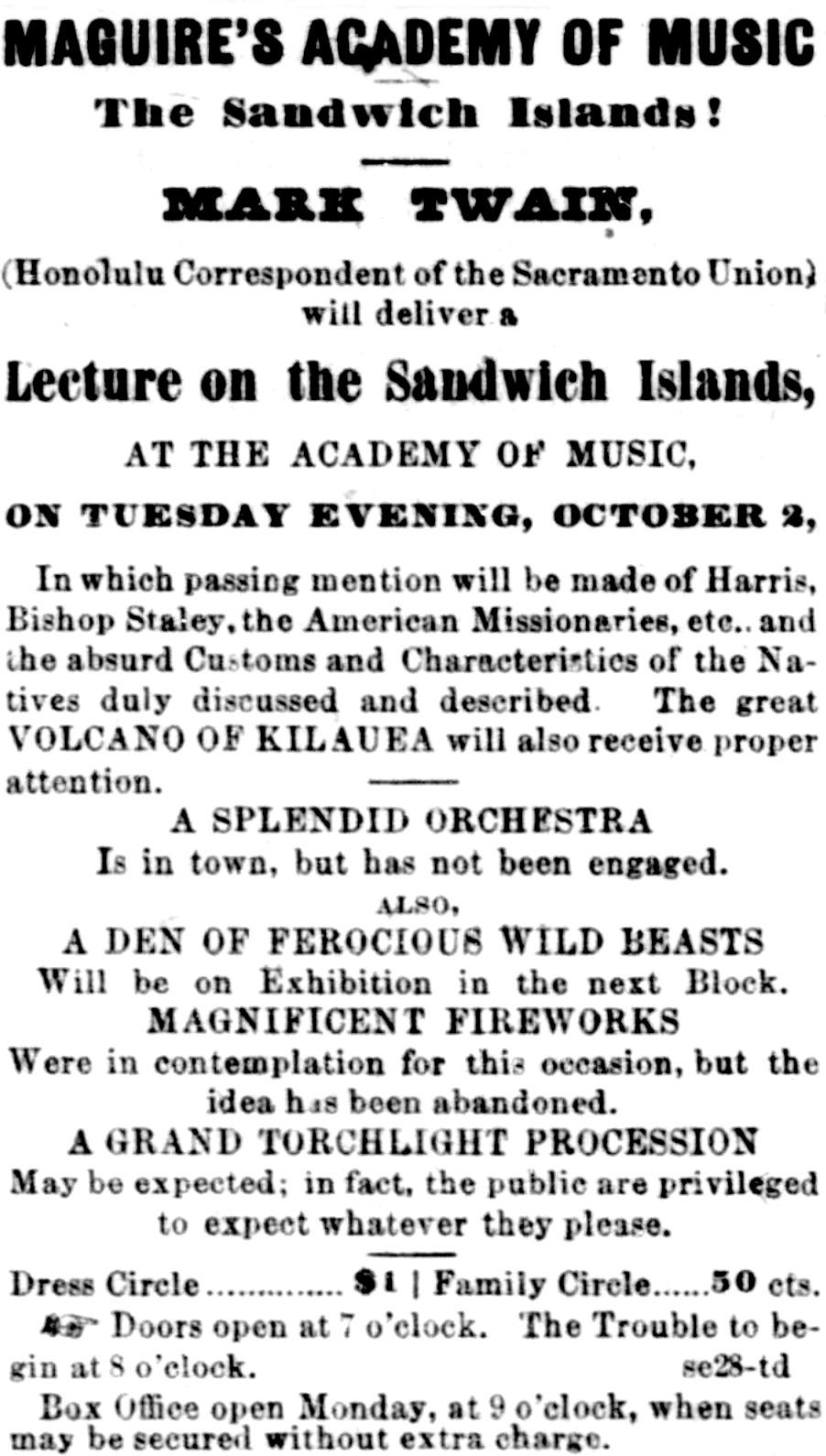

For one thing, the journalist decided to try lecturing. Traveling around California and Nevada with a presentation about Hawaii (then called the Sandwich Islands), he pleased some audiences and disappointed others while he slowly learned a new craft of public speaking. Each audience taught him something more. The San Francisco papers glowed with praise. The Sandwich Islands lecture, pronounced the Chronicle, “may be pronounced one of the greatest successes of the season.”

A second development was attention from a higher class of persons. He dined with ministers and entertained dignitaries such as the governors of California and Nevada. He seemed to be following the advice that one early biographer said he received from Anson Burlingame, U.S. minister to China. “I believe you have genius,” Burlingame allegedly told the young journalist. “What you need now is the refinement of association. Seek companionship among men of superior intellect and character. Refine yourself and your work. Never affiliate with inferiors; always climb.” After voyaging in company with the heroic Captain Mitchell and his gentlemanly passengers, the journalist was ready to take Burlingame’s advice.

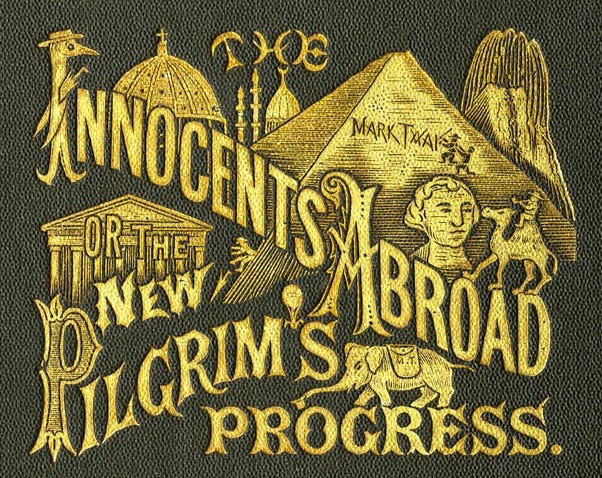

The journalist left California for the eastern States in December. The next summer, he boarded a steamship that advertised a transatlantic pleasure cruise to the Mediterranean. A San Francisco newspaper had engaged him as a correspondent. Following Burlingame’s advice, he associated with social superiors and sought feedback from them about his writing. In this next set of travel letters, his style showed much more confidence than in 1866. No more did he try to inform his readers about a place with interjections of amusement; he had committed to the style of a humorist first and last.

His letters from the Holy Land were a hit in California, and the book he compiled from them (with extensive advice from those social superiors) became the bestseller, Innocents Abroad (1869). Its theme was encapsulated in this line: "The gentle reader will never, never know what a consummate ass he can become, until he goes abroad."

If we are to judge by the rise in the author’s fortune and reputation, it was not the Hornet story in Harper’s Monthly but the publication of Innocents Abroad, the travel book from the Holy Land, that demonstrated the maturation of the western humorist’s literary voice and style.

Brilliant storyteller that he was, Sam Clemens knew there was no drama in describing the origins of his career as years of patience, toil, and uncertainty. Of trying, failing, and trying again. Better to tell his readers that his literary career began with a dramatic survival story and a wild piece of luck.

But even Mark Twain was given no shortcuts. It took more than a single good story to build a career. It took talent, yes, but also persistence.

“Forty-Three Days in an Open Boat” did not send Mark Twain up to literary glory, but the company of the remarkable survivors may well have transferred to the impoverished journalist some subtle fume he needed of hardihood and faith.

He went back to the writing table and tried again.

Sources & Related Reading

David Fears, Mark Twain Day by Day. Digitized by the Center for Mark Twain Studies at https://daybyday.marktwainstudies.com/. (Much detail in this article comes from the 1866 section of this remarkable scholarly resource, until recently only available in print.)

Mark Twain’s Letters, vol. I, ed. Edgar Marquess Branch, et al. (University of California Press, 1988). Digitized by the Mark Twain Project.

Gary Scharnhorst, The Life of Mark Twain. The Early Years, 1835-1871. (University of Missouri Press, 2018). pp. 337-345. Google Books Preview.

Gary Scharnhorst, “Mark Twain Reports the Hornet Disaster,” American Literary Realism, vol. 47, no. 3 (Spring 2015), pp. 272-276. (Scharnhorst is the biographer who fact-checked the impression Twain gave his readers about the influence of his Hornet reporting, finding it to be exaggerated.) Link to article at Project Muse (probably paywalled)

Gary Scharnhorst, ed., Twain in His Own Time: A Biographical Chronicle of His Life (University of Iowa Press, 2010). Google Books Preview.

Mark Twain, “My Début as a Literary Person” (1900). (A delightful read - recommended. You’ll see that Twain himself was clearly tongue-in-cheek and a little extravagant in referring to his ‘literary’ début. Early biographers might have been more cautious taking him so much at his word.)

*

Find more hidden stories about authors familiar and unfamiliar at the section of my home page called “The Once and Future Author.”

What? It’s Monday again? How did this happen?

Regular readers will remember my intention to move Quiet Reading from a Monday publication to Fridays. Evidently that will not be accomplished in a snap. It is going to require slow effort, like the launch of Mark Twain’s career. Fans of Mark Twain can have fun laying wagers as to which Friday makes the change.

Your Turn

Mark Twain scholars know the Hornet story well. At what point did you recognize that we were talking about Twain?

Have you read Percival Everett’s “James” yet - the 2024 novel that retells Mark Twain’s classic, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn?

Was there a dramatic incident in your life or career that you thought would be more significant, but in the long run, it wasn’t?

Have you been to Kilauea or another volcano in person? What was it like?

Had a hunch it was Twain from early on, though I couldn't really say why, since I didn't actually know the Hornet story. Among many other things, the man had a knack for self-promotion.

I have read James, in fact, and reviewed it here: https://www.nationalreview.com/2024/04/huck-finn-revisited/.

GRACIAS QUIET READING